Volume VI, Issue 5

Author: Beloo Mehra

The attempt to express in form and limit something of that which is formless and illimitable is the attempt of Indian art.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 8, p. 64

Art historian Stella Kramrisch states that the art of painting has played an important role in the life of the Indian people since ancient times. Perhaps this is why it led them to invent creative legends to explain the origin of this art. The Vishnudharmottara, an appendix to Vishnu Purana, links the origin of painting with the very act of creation.

Once the great sage Narayana was deeply engrossed in his meditation. At some point he discerned the motive of apsaras who were trying to distract him. And in a moment of high inspiration he drew the most beautiful female figure on the ground. The woman soon came alive, and having seen her divine beauty, the apsaras went away in shame. The woman became known by the name Urvashi.

Citralaksana is one of the earliest treatises on Indian painting. The only surviving copies of this text are in Tibetan language. As per a legend in Chitralaksana, a King and his kingdom were steeped in sorrow at the death of the high priest’s son. Everyday the king prayed to Lord Brahma. Moved by the king’s prayer, Brahma asked him to paint a portrait of the boy on the floor so that he could breathe life in to it.

These tales underline the belief in the life-giving power of the art of painting.

The Long Tradition of Indian Painting

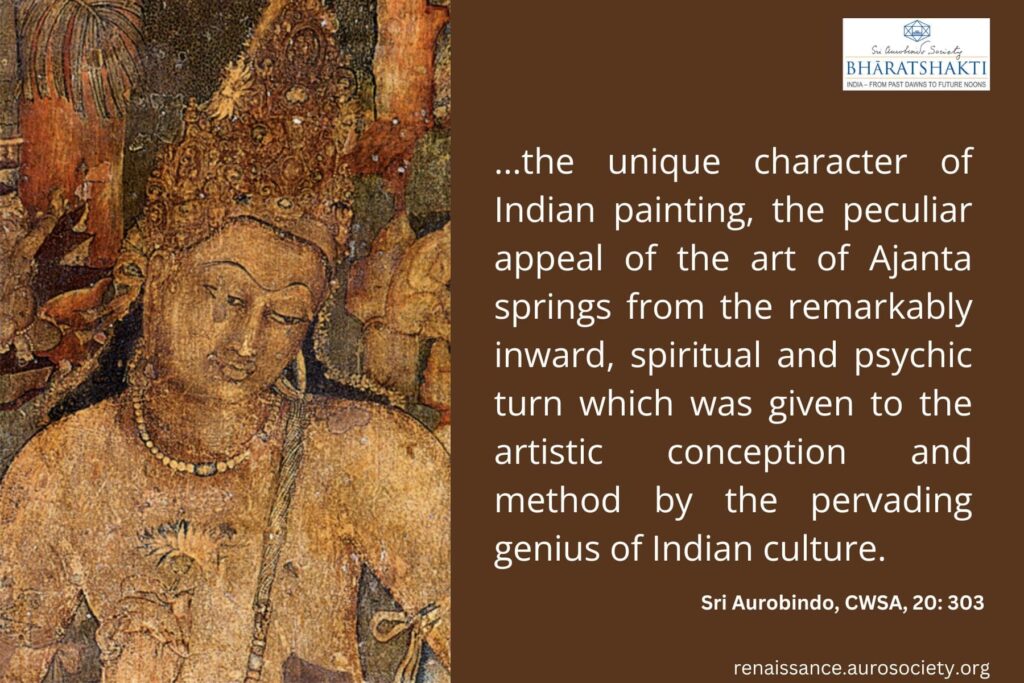

Painting is naturally the most sensuous of the arts, and the highest greatness open to the painter is to spiritualise this sensuous appeal by making the most vivid outward beauty a revelation of subtle spiritual emotion so that the soul and the sense are at harmony in the deepest and finest richness of both and united in their satisfied consonant expression of the inner significances of things and life.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 302

The journey of Indian painting begins with the earliest stone age rock paintings and moves to the patterns found on excavated seals and pottery right up to the modern-day rangoli and kolam patterns. Along the way, it covers hundreds of painting traditions across the length and breadth of India. It has traveled from Bhimbetaka cave art to classical frescoes of Ajanta, from the bold and beautiful Thanjavur or Mysore styles to richly detailed Vijayanagara style, from delicate lines of Pahadi and Rajput miniatures to the imitative Company school.

Then there is also the journey from the academic realism of Raja Ravi Varma to the search for a new Indian style — modern yet rooted in the timeless Indian cultural spirit — in the Bengal school of Abanindranath Tagore. And from the contextual modernism of Rabindranath Tagore’s Kala Bhavan to Progressive school of S. H. Raza, M.F. Hussain, Ram Kumar. Then come some of the present-day artists inspired by modernism of Baroda School and others.

Also read:

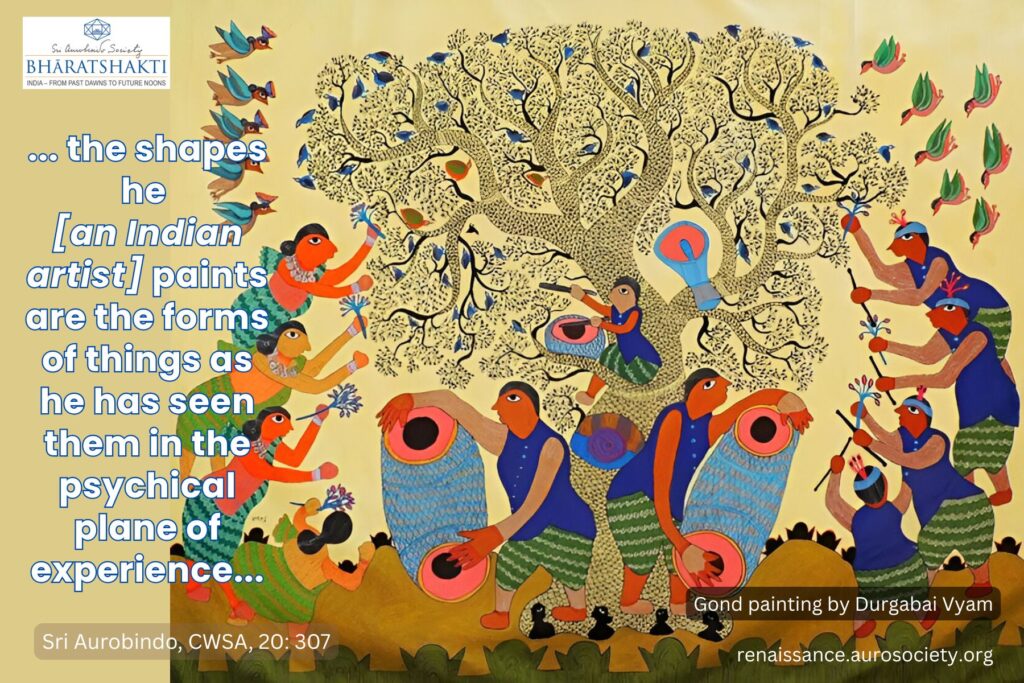

Sri Aurobindo on the Art of Painting in India

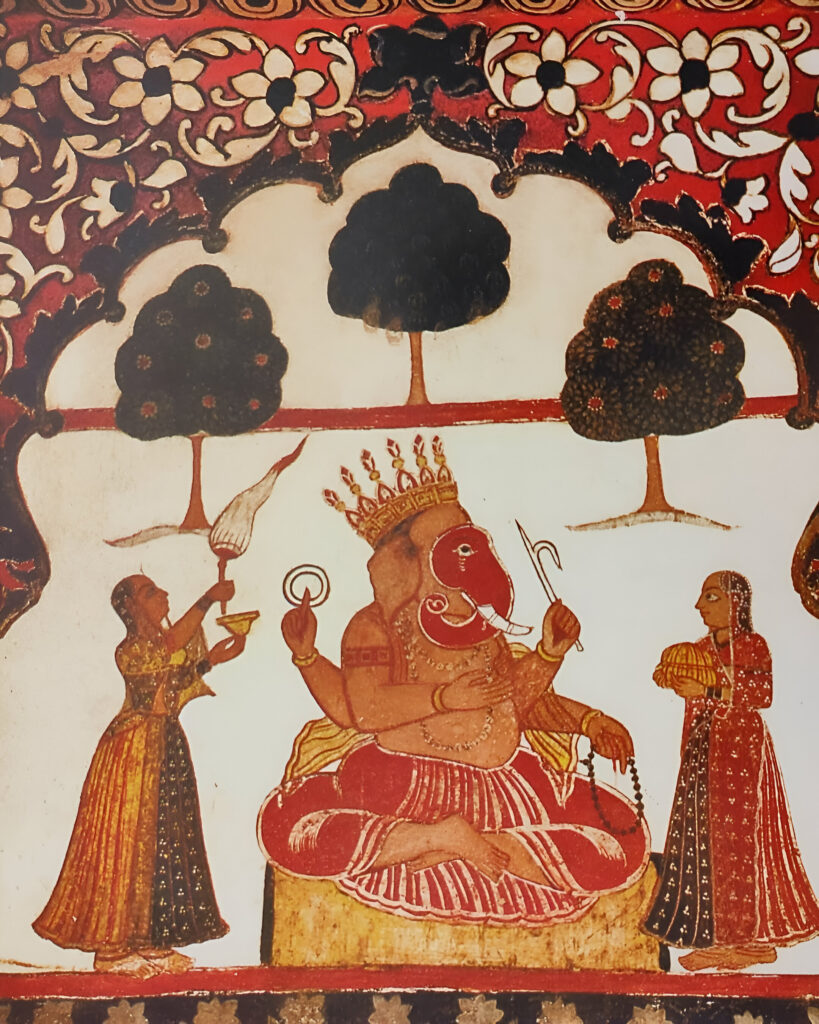

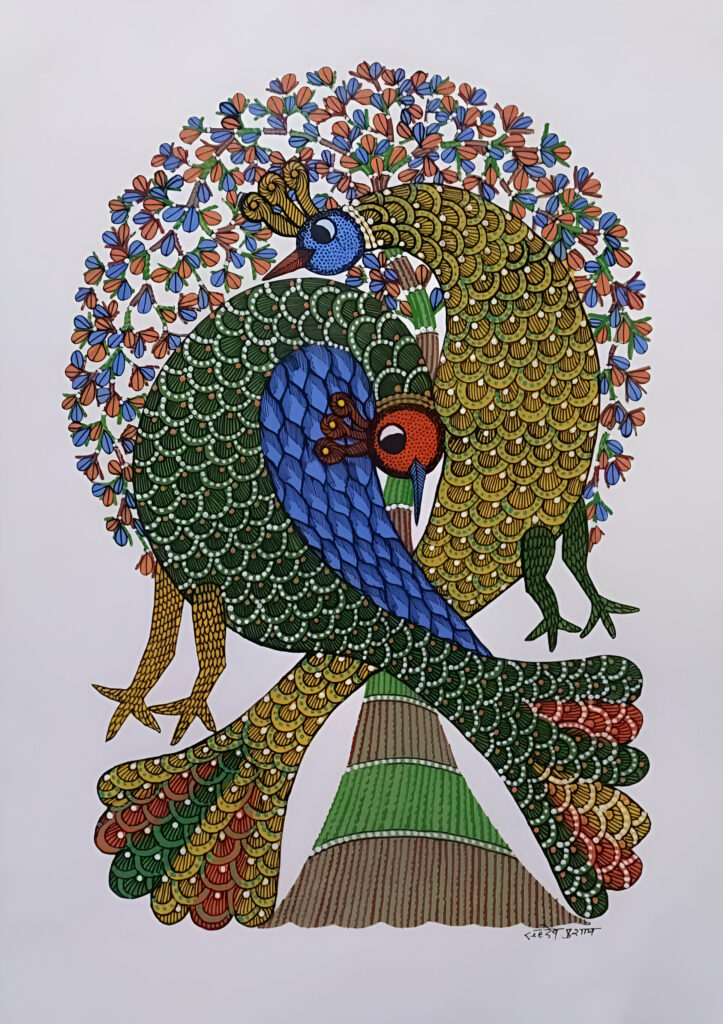

In between all these, the richly flourishing folk art traditions — specific to each region of the country — have continued to fill the aesthetic landscape of India. They express the lived realities of people and folklore through vibrant colours and bold lines, as well as the highest religio-spiritual truths integrated with their day-to-day life. These diverse painting traditions — from Pattachitra to Patua, Gond and Bhil to Phad and Pichai, Madhubani to Warli, Bundeli Kalam to Kalamkari, Mata ni Pachedi to Cheryl, and many more — each having their own multiple variants, continue to thrive and innovate to this day.

The Motives of Painting in India

Throughout its long history, Indian painting has understood that to illustrate life and Nature is only the first and primitive object of art. In great hands, Indian painting has risen to a revelation of the glory and beauty of the sensuous appeal of life, or of the dramatic power and moving interest of character, emotion and action.

Indian painting over the ages was not only based on religious themes. It was always reflective of the culture that existed at each point of time. This was true in the prehistoric age of spearmen, or when Buddha walked the earth. And also when the elites of Ashoka’s empire or the indomitable chieftains of the hill kingdoms ruled and warred. Indian painting expressed all these themes.

But even from behind the most mundane or the most profuse depictions of human nature and culture, the Indian painter attempted to convey a deeper significance, a spiritual flavour, a hint of the unseen. The true appreciation of Indian painting must, therefore, be in the light of its second and more elevated aim. This aim is, in fact, the starting-point of the Indian motive of art. That motive has to do with the interpretation or intuitive revelation of existence through the forms of life and Nature. Sri Aurobindo describes this motive of painting as “to spiritualise the sensuous appeal”. To appreciate such a painting, we must have an inner psychic or spiritual vision awakened in us.

Our ancients saw the potency and value of painting. It was neither merely an entertainment, nor meant to only illustrate life and nature. It was, at its highest, a means to connect with the unseen. Painting can create a bridge between the known and the unknown, a way to express the unseen.

Indian Treatises on Painting

According to Vishnudharmottara, paintings instruct and enliven the mind of the people as permanent or temporary decoration on the floors, on the walls and ceilings of private houses, palaces, temples, and in the streets. Like all other arts in India, over its long history the art of painting also became highly systematised. And a number of shastra-s devoted to painting were composed to document as well as formalise the tradition and suggest new experimentation.

Among the Śilpa Shastras, we have Narada Śilpa Shastra (chapters 66 and 71 are dedicated to painting), Saraswati Śilpa Shastra which describes various types of chitra (full painting), ardhachitra (sketch work), chitrabhasa (communication through painting), varna samskara (preparation of colours). The key treatises codified after the Ajanta experience (earliest paintings at Ajanta were made circa second century BCE) include:

- Brihat-samhita (6th century)

- Kamasutra (6th century)

- Vishnudharmottara (7th century)

- Samarangana-sutradhara (11th century)

***

Kamasutra speaks of ‘sadanga’ or Six Limbs of Painting, which are found to be common elements in all great works of art. These six limbs are:

- Rūpabheda – the distinction of forms

- Prāmanam – proportion, arrangement of line and mass, design, harmony, perspective

- Bhāva – the emotion or aesthetic feeling expressed by the form

- Lāvanya – infusion of grace the seeking for beauty and charm for the satisfaction of the aesthetic spirit

- Sādrysam – resemblance, truth of the form and its suggestion

- Varnikābhangam – the turn, combination, harmony of colours

These are the first constituents to which every successful work of art reduces itself in analysis. But as Sri Aurobindo explains in the Guiding Light feature of this issue, it is the turn given to each of the constituents which makes all the difference in the aim and effect of the technique and the source, and the character of the inner vision guiding the creative hand in their combination which makes all the difference in the spiritual value of the achievement.

The Greeks, aiming at a smaller and more easily attainable end, achieved a more perfect success. Their instinct for physical form was greater than ours, our instinct for psychic shape and colour was superior. Our future art must solve the problem of expressing the soul in the object, the great Indian aim, while achieving anew the triumphant combination of perfect interpretative form and colour.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 8, p. 64

In This Issue

We feature in 2 parts, selections from Sri Aurobindo which give us a deeper historical overview of the art of painting in India, especially focusing on its continuity. He speaks of the deep and intimate connection of Indian painting with the spiritual and religious-philosophic vision that is at the source of all Indian cultural expressions.

In Part 3 of the series on Veerabhadra Swami Temple at Lepakshi, we focus our attention on the magnificent murals. We see most of these in the temple’s natya mandapa. They portray stories from our itihāsa-s and purāna-s, and mesmerise us with their aesthetic appeal even after more than 500 years. At the same time, they also help us get acquainted with some of the social-cultural-political practices of that time. Looking carefully at these paintings we also get a good idea of the contemporary fashion trends.

Jishnu Guha writes a brief biography of Nandalal Bose, a pioneer of what came to be known as Contextual Modernism school of Indian painting which emerged from Shantiniketan. He focuses on the various artistic, philosophical and spiritual influences that shaped Nandalal Bose as an artist.

In part 2 of Sri Aurobindo and Indian Aesthetics, we include a few videos inspired by Sri Aurobindo’s poems. The author speaks of these poems as examples of the Indian aesthetic vision as reflected in Sri Aurobindo’s literary work. In a new episode of Insightful Conversations at BhāratShakti, we speak with Chad Kilgore, a US-based visual artist, on his journey as an artist, his spiritual quest, and the relation between his art and his inner journey.

More than Art

In Children’s Corner, we feature a short tale on Self-control. In addition to the English translation as told by the Mother, we present the Hindi translation in the form of an animated video. Video editing and voice-over are done by Biswajita Mohapatra.

For Book of the Month, Dr. Nanda Kishor M S from Pondicherry University writes a review of Antaryatra: Soul Journeys (authored by yours truly). Chair of Sri Aurobindo Studies and Head, Department of Politics and International Relations, he describes the book “as much a call to rediscover India’s inner truths as it is an invitation for the reader to walk the path of inner awakening”. The recording of the review is also included.

We hope our readers will enjoy going through the various offerings in this issue. As always, we offer this work at the lotus feet of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother.

In gratitude,

Beloo Mehra (for Renaissance Editorial Team)