Volume II, Issue 5

Author: Beloo Mehra

Editor’s Note: A wider view of Indian cultural forms suggests that Rām-kathā continues to thrive as an important influence despite the outer hybridity in Indian popular cultural landscape.

यावत्स्थास्यन्ति गिरयः सरितश्च महीतले |

तावद्रामायणकथा लोकेषु प्रचरिष्यति ||

“As long as the mountains and rivers flourish on the surface of the earth, so long the legend of Rāmāyana will flourish in this world.” [Vālmiki Rāmāyana, 1.2.36]

For thousands of years, Rāmāyana has been a living literary and cultural tradition of our land. In fact, it also went beyond the land of Bhārat and captured the cultural imagination of many parts of South-east Asia.

The two itihāsa-s influenced much of the literature and art in India. Listed below are a few gems from the great body of classical Sanskrit literature which drew its inspiration from the stories of the Rāmāyana:

- Bhāsa, who was one of the earliest known Sanskrit dramatists based his Pratima Nataka and Abhisheka Nataka on themes from the Rāmāyana. The Pratima Nataka sought to dramatize almost the entire story of the Rāmāyana in seven acts, putting characters of Bharata and Kaikeyi in spotlight. The Abhiseka Nataka narrated events from the slaying of Vali and the coronation of Sugreeva and concluded with the Abhiseka of Rama.

- Among the mahākavi Kālidāsa’s works we have his epic poem Raghuvamśa about the ‘dynasty of Raghu.’ In Raghuvamśa, he describes Rama as Ramabhidhano Hari, Hari known as Rama.

- Bhavabhūti’s Uttararāmacharita (‘The Later Deeds of Rama’) continues the story of Rāma from the time of his coronation to the banishment of Sitā and their final reunion. This work has been applauded for its rare sensitivity since it zooms in on Sitā’s story as an individual, focusing on her feelings of doubt about Rāma’s love, her anger at her banishment, long suffering and the revival of her capacity for love – all of which have been treated with due consideration and sensitivity.

Over time as literature in various regional languages of India came to its own, we had more retellings in narrative poetry of the story of the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyana. This fulfilled a cultural necessity by transferring into the popular speech of various regions the central story of the two itihāsa-s, also sometimes focusing on some important episodes and sometimes on other legends and stories which were embedded in the original epic poems.

The various retellings of Rāmāyana across India in different languages helped unite the Indian collective consciousness in an organic and deeper way. One prominent work of narrative poetry inspired by the Rāmāyana is that of Krittibas – written with a simple poetic skill and a swift narrative force.

But the supreme masterpieces which are vividly living recreations of the ancient story are: 1) The Rāmāyana of Kamban, the Tamil poet who makes of his subject a great original epic; 2) and the Rāmcharitmānas of Tulsidās in Avadhi, which Sri Aurobindo remarks, “combines with a singular mastery lyric intensity, romantic richness and the sublimity of the epic imagination and is at once a story of the divine Avatār and a long chant of religious devotion.” (CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 381)

The Buddhist and Jain versions of the Rāmāyana spoke of the story of Dasharatha and Rāma in ways quite different from Vālmiki’s or others based on his version.

The Rāmāyana became a thread to bind various regional cultures with bhakti and love for Rāma and Sītā. Plenty of literary, sculptural and epigraphic evidence is there to suggest that by the fourth-fifth century CE, the worship of Rāma as God incarnate had been well-established throughout India.

To this day, the story of the Rāmāyana and its various characters have captured the imagination of writers across various languages within and outside India. We continue to witness thriving traditions of Rām-kathā and Rāmlīla in various parts of the country, especially during the holy days of Navaratri. Indians have been reciting, listening to or watching enactments of Rām-kathā for thousands of years; and these traditions not only continue to flourish but with the advent of online technologies we are also witnessing newer forms of retelling of the stories of Rāmāyana.

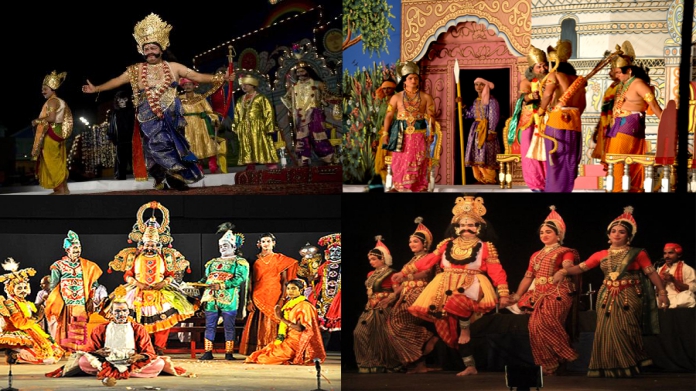

Rāmāyana in Indian Folk Theatre

Rāmlīla as an important folk theatrical tradition of India is believed to have originated in northern India in the 16th century. This was after Sant Tulsidās’s Rāmcharitmānas written in Avadhi language brought a fresh wave of devotional spirit in northern India and captured the collective mind of people through its portrayal of the ideal of Maryadā Purushottama Rāma. However, a tradition of Rāmāyana-based performance already existed in the form of public recitations of Valmiki’s Ramayana in Sanskrit. But it was after 1625 CE, dramatized adaptations of Tulsidās’ Rāmcharitmānas began to catch on, under the influence of Tulsidās’ student Megha Bhagat.

In many parts of northern India, as part of the annual celebration of Dussehra, Rāmlīla-s are typically performed as a cycle of episodes over the course of several nights of the Navaratri. In some cases, professional troupes are contracted to perform for a village or community. The traditional Rāmlīla was recognised by UNESCO in 2005 as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Many other folk theatrical traditions in India also draw inspiration from the stories and legends of the Rāmāyana. For example, Dashavātar, the most developed theatre form of the Konkan and Goa regions, performed mostly by farmers focuses on stories of various incarnations of Lord Vishnu, and Rāma’s story gets much prominence.

Koodiyaattam from Kerala is one of the oldest traditional theatre forms of India and follows the performative principles of the ancient tradition of Sanskrit drama. Recognized in 2001 by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, many Koodiyaattam performances are based on the stories from the Rāmāyana, the Mahābhārata and the purānas.

Ramman is a ritual theatre form unique to the twin villages of Saloor-Dungra in the Garhwal region of Uttarakhand. Every year in late April, it is performed as part of the religious festival in honour of the village deity, Bhumiyal Devta. It is neither replicated nor performed anywhere else in the country. Ramman is made up of highly complex rituals that involve the recitation of a version of the Rāmāyana and various other legends. This ritual theatre form which also involves use of masks was recognised by UNESCO in 2009 as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Yakshagāna, the famous folk theatre of Karnataka has a long history of nearly four hundred years. The performances are generally based on stories from the two epics and purānas. Episodes from the Mahābhārata such as Draupadi Swayamvar, Subhadra Vivāh, Abhimanyu Vadh, Karna-Arjun Yuddh, and Rām-abhishek, Luv-Kush Yuddh, Bāli-Sugreeva Yuddh and Panchavati from the Rāmāyana are commonly enacted. The performance – traditionally presented from dusk to dawn – is a unique harmony of music, eye-catching costumes, dance, improvised gestures, and acting with spontaneous dialogue.

Rāmlīla in Modern India

Around Navaratri and Dussehra I am often reminded of my growing up years in Delhi when I enjoyed the Rāmlīla in our neighbourhood. Over the years that local Rāmlīla has gone bigger and more elaborate, with big sponsors and bigger budgets. But more than that neighbourhood Rāmlīla, I look back fondly at the famous Rāmlīla performance at Shriram Bharatiya Kala Kendra. The Kendra has been organising and staging a dance drama based on the Rāmāyana for more than 60 years. For many years now, the show is simply called ‘श्रीRam’.

The Kendra in Delhi has done a great service to theatre arts in India by continuously staging a spectacular dance drama every year during the Navaratri. This grand show has not only been thriving but gaining wider appeal, offering a wonderful mix of various theatre arts and value-based entertainment to those interested. The three-hour show is repeated on all the nine evenings of Navaratri and also on several nights beyond Dussehra. For the last many years they have incorporated wonderful use of technology in the whole show.

The increasing popularity of ‘श्रीRam’ show over the last 60 years is an example of how a cultural tradition which continues to offer real value to people through its uplifting and elevating spirit can be easily renewed in its outer forms and yet enthrall the changing aesthetic preferences over time, provided there are people devoted to the true spirit or core of what the tradition represents in the first place.

Shobha Deepak Singh, the person in-charge of keeping the Rāmlīla tradition alive and thriving at Shriram Bharatiya Kala Kendra, comes from a strong family background which had Rām-bhakti at its center. She has often said that she has been reading Rāmāyana every day for the last 50 years; for her Rāmāyana is not a mythology but a ‘way of life.’ She has imbibed the spirit of what the charitra of Rāma means for herself and the larger humanity. She has said in her interviews that while the outer form of the Rāmlīla show at the Kendra has evolved over the years, she is committed to portraying the essential spirit of Maryāda Purushottama Rāma through the show.

Same can be said for Ramanand Sagar, the producer-director of TV Rāmāyana in 1980s, which was another modern variation of the old Rāmlīla tradition. He too had been a sincere devotee of Sri Rāma and it was his deep love for Rāma that came through his mega production of the TV serial which went on to change the history of television in India. The recent records made by the TV show in 2020 once again prove that the force of such value-based and culturally rooted theatrical traditions still goes on strong in the collective mind of Indians.

The continued popularity of the dance drama ‘श्रीRam’ of Shriram Bharatiya Kala Kendra and phenomenal success stories like the TV Rāmāyana don’t just happen only because of effective advertising and marketing power behind these mega productions. Or merely because of the rampant commercialisation of everything including religion (though commercialisation is an undeniable fact of our times). Or merely because there is a growing display of outer religiosity in contemporary social-cultural-political fabric.

The real and deeper reason lays hidden behind the outer phenomenon. There is always some drop of timeless truth working from behind which makes such phenomena happen. And that truth is the Truth of the avatārhood of Rāma.

Avatārhood of Sri Rāma

In Essays on the Gita, Sri Aurobindo explains that the purely practical, ethical or social and political mission of the avatār which is thrown into popular and mythical form, does not give a right account of the phenomenon of avatārhood because it does not cover the spiritual sense of the purpose of avatārhood. He adds that by giving only a religious sense to the word ‘dharma’ in which it means a law of religious and spiritual life, we get closer to heart of the matter, but there also we may miss out on the most important part of the work done by the avatār. Describing the double work of an avatār, he writes:

“Always we see in the history of the divine incarnations the double work, and inevitably, because the Avatar takes up the workings of God in human life, the way of the divine Will and Wisdom in the world, and that always fulfils itself externally as well as internally, by inner progress in the soul and by an outer change in the life. . .

“. . . the life of Rama and Krishna belongs to the prehistoric past which has come down only in poetry and legend and may even be regarded as myths; but it is quite immaterial whether we regard them as myths or historical facts, because their permanent truth and value lie in their persistence as a spiritual form, presence, influence in the inner consciousness of the race and the life of the human soul.

“Avatarhood is a fact of divine life and consciousness which may realise itself in an outward action, but must persist, when that action is over and has done its work, in a spiritual influence; or may realise itself in a spiritual influence and teaching, but must then have its permanent effect, even when the new religion or discipline is exhausted, in the thought, temperament and outward life of mankind. . .

“The Avatar comes to reveal the divine nature in man above this lower nature and to show what are the divine works, free, unegoistic, disinterested, impersonal, universal, full of the divine light, the divine power and the divine love. He comes as the divine personality which shall fill the consciousness of the human being and replace the limited egoistic personality, so that it shall be liberated out of ego into infinity and universality, out of birth into immortality. He comes as the divine power and love which calls men to itself, so that they may take refuge in that and no longer in the insufficiency of their human wills and the strife of their human fear, wrath and passion, and liberated from all this unquiet and suffering may live in the calm and bliss of the Divine.”

(CWSA, Vol. 19, pp. 168-176)

Keeping this in consideration let us see what has been the persistent spiritual influence of the avatārhood of Sri Rāma on the evolving consciousness in humanity. If we don’t contemplate on this, we fail to fully grasp why Sri Rāma’s story will be told over and over. Sri Aurobindo described the deeper significance of Rāma’s work in these words:

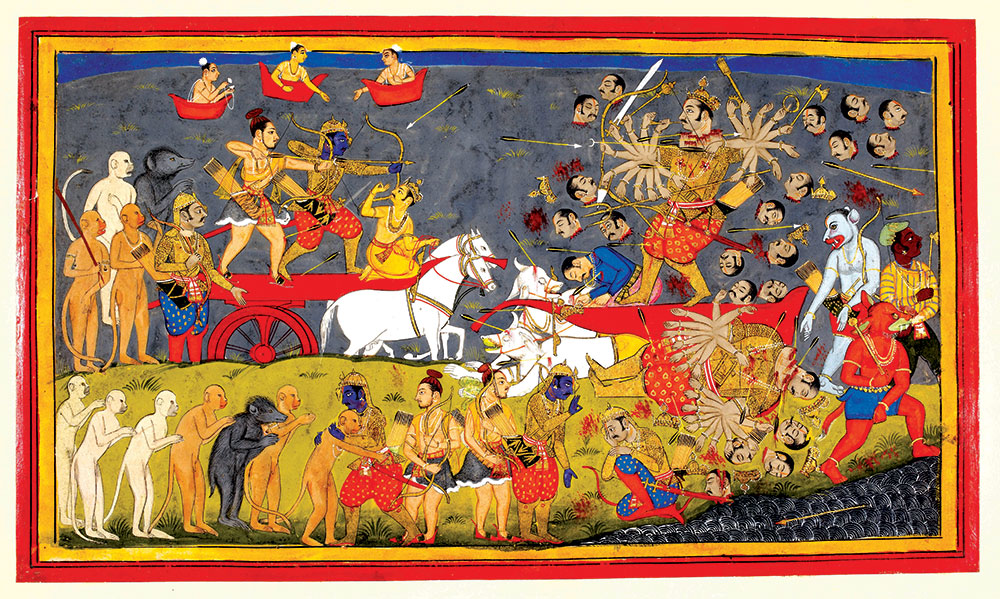

“[Rāma’s] business was to destroy Ravana and to establish the Ramarajya – in other words, to fix for the future the possibility of an order proper to the sattwic civilised human being who governs his life by the reason, the finer emotions, morality, or at least moral ideals, such as truth, obedience, co-operation and harmony, the sense of domestic and public order, – to establish this in a world still occupied by anarchic forces, the Animal mind and the powers of the vital Ego making its own satisfaction the rule of life, in other words, the Vanara and Rakshasa. . . .

(CWSA, Vol. 28, pp. 491-492)

“It was not his business to be necessarily a perfect, but a largely representative sattwic man, a faithful husband and a lover, a loving and obedient son, a tender and perfect brother, father, friend – he is friend of all kinds of people, friend of the outcaste Guhaka, friend of the Animal leaders, Sugriva, Hanuman, friend of the vulture Jatayu, friend even of the Rakshasa Vibhishan.

“All that he was in a brilliant, striking but above all spontaneous and inevitable way, not with a forcing of this note or that…., but with a certain harmonious completeness. But most of all, it was his business to typify and establish the things on which the social idea and its stability depend, truth and honour, the sense of Dharma, public spirit and the sense of order.

“To the first, to truth and honour, much more even than to his filial love and obedience to his father—though to that also—he sacrificed his personal rights as the elect of the King and the Assembly and fourteen of the best years of his life and went into exile in the forests. To his public spirit and his sense of public order (the great and supreme civic virtue in the eyes of the ancient Indians, Greeks, Romans, for at that time the maintenance of the ordered community, not the separate development and satisfaction of the individual was the pressing need of human evolution) he sacrificed his own happiness and domestic life and the happiness of Sita. In that he was at one with the moral sense of all the antique races, though at variance with the later romantic individualistic sentimental morality of the modern man who can afford to have that less stern morality just because the ancients sacrificed the individual in order to make the world safe for the spirit of social order.

“Finally, it was Rama’s business to make the world safe for the ideal of the sattwic human being by destroying the sovereignty of Ravana, the Rakshasa menace.”

On an outer level we know the story of the Rāmāyana as the victory of good over evil, dharma over adharma. But on an inner level we may also recognise that the two extremely opposite temperaments embodied by Rāma and Rāvana are essentially powers of mental nature – of excessive, dominating, violent egoism, and of a harmonising, ethical, sāttvic, gentle temperament. And the outcome is a decisive victory of the divine man over the Rākṣasa.

To go deeper, let us see what a Rākṣasa (राक्षस) actually means. The term is generally translated as a demon, someone who is an evil or malignant being. According to Sri Aurobindo, the Rākṣasa is the supreme and thoroughgoing individualist, who believes life to be meant for his own untrammelled self-fulfilment and self-assertion.

In opposition to a Rākṣasa is the daivic being, one with daivic nature, a Deva. While the Deva (देव)is generally translated as a heavenly being, shining one, divine, a deity or god; according to Sri Aurobindo, the Deva, stands firm in the luminous heaven of self-knowledge; his actions flow not inward towards himself but outwards toward the world.

This important difference helps us understand the significance of the main narrative of Rāmāyana, the victory of Rāma over Rāvana, in a deeper truer sense.

When we thus understand the Truth of avatārhood and the purpose for which the avatār of Sri Rāma descended on earth, we begin to see how through his work, through his life’s example Sri Rāma worked tirelessly to establish the supremacy of ethical-aesthetic-moral mental consciousness over the physical and the vitalistic. Following his swadharma, kula-dharma, jāti dharma, and dharma of his time and age, he worked to establish a society based on the ideal of Dharma. That is why he continues to remain relevant for today, tomorrow and for times to come. And his kathā continues to hold significant place in the collective cultural mind of India and beyond.

[Rama’s] figure has been stamped for more than two millenniums on the mind of Indian culture and what he stood for has dominated the reason and idealising mind of man in all countries—and in spite of the constant revolt of the human vital is likely to continue to do so until a greater Ideal arises.

(CWSA, Vol. 28, p. 492)

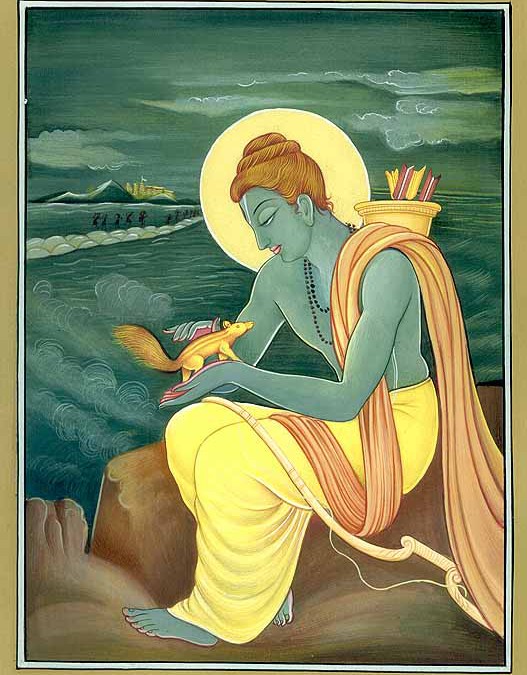

~ Cover painting: Hanuman Revives Rama and Lakshmana with Medicinal Herbs

Illustrated folio from a dispersed Ramayana series, ca. 1790

(credit: Met Museum)