Editor’s note: As part of India’s intellectual decolonizing project, it is critical to incorporate Sri Aurobindo’s vision and thought in academia and mainstream intellectual discourse. This can be just the right foundation for facilitating an original discourse. While being grounded in India’s ancient spiritual wisdom, his vision speaks of future India and her mission for the world and humanity.

The author underlines for us some of the key ideas of Sri Aurobindo that could be taken forward for further treatment in academia, both present and future. He also addresses a fundamental question about the connection between development of the intellect and yogic consciousness.

This article was first published in August 2023 issue of SABDA Newsletter.

The most direct path to catastrophe is to treat complex problems as if they are obvious to everyone.

—Stephen Marche on the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Chat Box

The significance of the lotus is not to be found by analysing the secret of the mud from which it grows here… you must know the whole before you can know the part… That is the province of the greater psychology awaiting its hour.

—Sri Aurobindo on modern psychology, CWSA, Vol. 31, p. 616

* * *

How does one make an estimate of Sri Aurobindo’s place in the modern academic world on his 150th anniversary? What are his singular contributions to intellectual history at the national and global level?

I shall argue that while the reception of Sri Aurobindo’s thought in the mainstream academia of India and the West may have undergone a change after his passing, and some academic disciplines may not be as hospitable to him as before, newer vistas like Global Studies, International Relations, Consciousness Studies, Cosmopolitanism, Indic Studies, and Integral Education may witness the growing influence of Sri Aurobindo in the academic world.

Like all institutions, the modern university system has undergone changes spatially and temporally in historical terms.

To talk about the reception of Sri Aurobindo without taking into account contextual and historical factors would not be a viable proposition. These dimensions, howsoever briefly, will figure into the present discussion.

A caveat is perhaps called for: there is no claim here that the viewpoint suggested in this article is definitive. Indeed, other approaches are possible with alternate readings of the reception of Sri Aurobindo in modern academia as we trace a future trajectory.

* * *

In his New Ways in English Literature (1917)1, Irish poet-critic James Cousins saw Sri Aurobindo as the harbinger of the poetry of the future. Aldous Huxley, the foremost novelist-thinker of the twentieth century, author of The Perennial Philosophy who had a great affinity with Indic traditions, cited the Master’s magnum opus The Life Divine as an extraordinary work of literature. Likewise, Nobel laureates Pearl S. Buck and Gabriela Mistral nominated Sri Aurobindo in 1949 for the coveted Nobel Prize in Literature.2

Similar nominations were made by a group of eminent Indian academics and men of letters in 1949 for the Nobel Prize in Literature.3 Harvard professors of philosophy in the late 1940s recognised the world vision of Sri Aurobindo in philosophical terms. Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, acclaimed philosopher-statesman of modern India and former President of the Indian Republic, called Sri Aurobindo ‘the greatest intellectual of our age’.4

On 11 December 1948, Sir C. R. Reddy, then Vice-Chancellor of Andhra University, bestowed upon the Master a special prize for ‘eminent merit in the humanities’.5 The distinguished historian R. C. Majumdar noted the outstanding contributions of Sri Aurobindo in the domain of Indian historiography,6 in particular the latter’s refutation of the so-called Aryan invasion theory that K. D. Sethna in later years would develop at considerable length in linguistic and archaeological terms.7

***

Leading poet-critics of modern Bengal like Buddhadeva Bose, in the post-Tagore phase, held up the poetry and poetic genius of Sri Aurobindo as exemplary models for the younger generation of Indian poets. Other litterateurs such as K. R. Srinivasa Iyengar, V. K. Gokak, C. D. Narasimhaiah, and Raja Rao, all doyens of modern Indian English literature, lavished praise on Sri Aurobindo. Dilip Kumar Roy, Kuvempu, Prema Nandakumar, and others added their admiration in later years.

The makers of modern India as well as leading politicians of all hues8 recognised Sri Aurobindo as a builder of modern India and his thought-vision worthy of study in the Indian university system. The authors of the two University Commissions in post-independence India, Dr. S. Radhakrishnan and Dr. D. S. Kothari, singled out the educational tenets of Sri Aurobindo’s thought as worthy pedagogic precepts and practices for university learners and young adults.

And yet Sri Aurobindo’s presence in mainstream Indian and Western academia today, barring notable exceptions, is evident by its absence.

Generations of students of Indian higher education know about the philosopher K. C. Bhattacharya’s idea of Swaraj, M. K. Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj, the works of Rabindranath Tagore, Jawaharlal Nehru, B. R. Ambedkar, and others. They know about the Western and Afro-Asian contributions to the decolonisation of the mind through the study of the works by Frantz Fanon, Edward Said, Noam Chomsky, and others. They have read with profit the slave narratives of the United States by Frederick Douglass, the Indian Subaltern historiography edited by Ranajit Guha, the works of Raymond

Williams, Jacques Derrida, Gayatri Chakrabarty Spivak, Michel Foucault, and Walter Benjamin.

But they do not hear the voice of Sri Aurobindo whose pioneering contributions in The Foundations of Indian Culture laid the ground for post-colonial studies.

They know about the translation theories of Susan Basnett, but not those of Sri Aurobindo, who had ably translated the Vedas,9 the Upanishads, and the Indian epics. Surely, this must be on account of the Eurocentric bias in our knowledge system as well as the continued cultural imperialism in the so-called third world.

Literature: Early Critics

In the sixties and early seventies of the last century, noted Indian English poets and critics such as P. Lal, Raghavendra Rao, Nissim Ezekiel, and Arvind Krishna Mehrotra joined issue with Buddhadeva Bose and found Sri Aurobindo’s poetic credo and practice lacking in inspiration for the younger poets in India. It was claimed that in order to appreciate Sri Aurobindo’s poetry, one had to be a disciple or a devotee like Iyengar, Gokak, or Sethna. In an interview, Mehrotra asked rhetorically: ‘Where was the sense of tradition going to come from? It was not going to come from Sarojini Naidu or Sri Aurobindo.’10

Similarly, P. Lal claimed that in reading Savitri, one ‘has the effect of a gushy, comical experience with alas no mystical movements which are “deeper than the deeps”’. He would change this unsympathetic viewpoint at a later period.11

Sympathetic voices contested such disparagement and made qualified responses.

For instance, in his insightful essay, ‘The Indian Imagination’, K. D. Verma, the former editor of a leading American journal, South Asia Review (SAR), declares that ‘Aurobindo is mostly known as a philosopher and a poet, but his stature as a critic remains somewhat unassured and deeply undervalued and perhaps overshadowed by the unsurpassed brilliance and originality of his work in other areas.’12 He adds, ‘One must say unhesitatingly that The Future Poetry is an important and unique document in literary history and critical theory.’

Verma surmises that Sri Aurobindo’s departure from England a ‘quarter of a century ago,’ and his ‘distance from contemporary English literature’ are possible reasons for his eclipse from the critical scene in India. Similarly, Narasimhaiah,13 while declaring Sri Aurobindo to be the ‘inaugurator of modern Indian literary criticism’, says, ‘For more than a century, he has not found a follower in a land celebrated for followers.’

Contextual Factors and Contested Categories

One must dispassionately look for deeper reasons for the relative absence of Sri Aurobindo in today’s mainstream academic and intellectual culture. Some of these reasons, one may argue, would be found by historicizing our account. The idea here is not to be reductive and exclusive, but to suggest possible explanations for the change in sensibility and worldview. And thereby we may discern possibilities for the future.

Fin-de-siècle Counter Culture

Post-colonial critic Leela Gandhi is correct in her assumptions in her pathbreaking book Affective Communities, 2009, that fin-de-siècle Europe and the Edwardian era in England generated worldwide interest in counter-culture movements in the domains of occultism, vegetarianism, theology, and

alternative living. D.H. Lawrence’s search for the ideal utopian commune in the deep Southwest of the United States led him to the company of the native American Indians of Taos, New Mexico.

The journey of James and Margaret Cousins took them to India at the invitation of the noted theosophist Annie Besant. The romantic-mystical poetry of AE, W. B.Yeats, Stephen Philips, Manmohan Ghose, Sri Aurobindo, Tagore, and others dealt with the subjective experience of the inner world.

***

The Bengal School of Art spearheaded by Nandalal Bose, Abanindranath Tagore, and art critics like A. C. Gangooly promised to usher in what Sri Aurobindo considered the subjective era in human civilisation, a new cosmology for the world.

However, by 1922 the publication of The Wasteland by T.S. Eliot and the rise of modernist-imagist poetry spearheaded by Eliot and Ezra Pound began a new movement in literary modernism in the Anglo-American world. Poetry must deal with commonplace, quotidian experience and capture the angst and anomie of modern existence, it was claimed.

Eliot, Pound, William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, and the ‘Movement Poets’ in England created newer modes of poetic idiom and sensibility. D.H. Lawrence, Philip Larkin and later poets like Ted Hughes influenced the newer generation of Indian English poets. A. K. Ramanujan, Dom Moraes, Adil Jussawala, Keki Daruwalla, Jayanta Mahapatra, Shiv K. Kumar, R. Parthasarathy, Arun Kolatkar, and others wrote poetry that dealt with the empirical experience, using a pronounced modernist idiom.

The reign of secular modernity and cultural Marxism in various disciplines led to the marginalisation of the earlier era of spiritual/mystical poetry and its underlying metaphysics and view of life.

The Subjective Nature of Critical Canons and Taste

Sri Aurobindo saw the reasons for such a bias in the domains of literature and culture. In a letter dated 5 October 1934, he wrote to a correspondent:

Most labour to fit their personal likes and dislikes to some standard of criticism which they conceive to be objective, this need of objectivity, of the support of an impersonal truth independent of our personality, or anybody else’s, is the main source of theories, canons, standards of art. But the theories, canons, standards themselves vary and are set up in one age only to be broken in another.

~ CWSA, Vol. 27, p. 663

Radical Changes in Academia, Challenges to Western Modernity, Insights from Sri Aurobindo

In varied measures, the dominance of literary modernism and the larger project of Western modernity were challenged by philosophies and movements beginning in the 1960s.

In language studies, the postulates of Ferdinand de Saussure were challenged by structuralism and post-structuralism in Western academia. The ‘language turn’ in literary-cultural theory and criticism came through Jacques Derrida, Paul de Man, Harold Bloom, and J. Hillis Miller. The work of Judith Butler, Julia Kristeva, Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, and others paved the way for the new era of cultural materialism and criticism. Meaning, cognition effect, and symbols came centre stage in the study of literature and culture.14

On the surface, the new paradigms may not share much with the Aurobindonian worldview. However, we may argue that Sri Aurobindo’s critique of Western modernity, anchored to the primacy of Reason and Rationality, merits the critical attention of scholars in the field. His twin essays in The Life Divine, 15‘The Methods of Vedantic Knowledge’ and ‘Reality and the Integral Knowledge’,16 have much to offer Western epistemology.

Language, Literature, Culture, and International Living: A New Cosmology?

The tech-centred world of today witnesses the blurring of the earlier boundaries between the word and the world, the text and the context. New Historicism, propounded by Harvard Professor Stephen Greenblatt, argues that historical truths must recognise ‘the inadequacy of stories told’ and that the study of multiple narrations could lead us closer to the so-called authentic account/narrative.

Language and self-reflexivity therefore become pivotal to such a critical enterprise. This is a truth that appears to be close to the Indic imagination, which lays a primary emphasis on the subjective experience, with language as a key category and determinant.

Its import and implications need to be explored further in the cross-cultural context.

In the domain of literature, concepts and platforms such as digital texts, graphic novels, graffiti work, meta-fiction, digital humanities, Instagram chatboxes, ethno-musicology, and medical, digital, and environmental humanities are increasingly becoming subjects of avant-garde research in the leading universities of the world.

Writing in the 6 December 2022 issue of The Atlantic magazine, Professor of Pedagogy Mike Sharples says that the undergraduate essay that has been at the heart of humanistic education in America is currently threatened by the open Artificial Intelligence (AI) chat box. Similarly, the novelist Stephen Marche argues that the blurring of distinction in the digital domain between mere opinion vis-à-vis grounded understandings necessarily leads us to ‘wilful obliviousness’.

One may, however, argue that contrary to prophets of doom, Literature and the Humanities are not doomed; nor does the Liberal Arts University face obsolescence. Marche adds prophetically: “The most direct path to catastrophe is to treat complex problems as if they are obvious to everyone.” As Steve Jobs declares, “It’s in Apple’s DNA that technology alone is not enough—it’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our heart sing,’ and ‘The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better the design we will have.”

Following the lead of figures like Stephen Marche, Mike Sharples, and Steve Jobs, we may say that the literary-cultural world, supported by newer visions of the university, must lead mankind towards a better and more harmonious future through a new cultural imaginary.

The new humanities in academia must address such concerns without being enslaved blindly to technology and consumer culture. Sri Aurobindo’s considered views are timely reminders about the pitfalls of a tech culture.

Academic Relevance of Sri Aurobindo

It is in this context that the neglected socio-cultural and global vision of Sri Aurobindo could pave the way for a new academic culture.

Sri Aurobindo shows an astute understanding of language and literatures of the world; he sees the seminal importance of multilingualism, of diversity and decentralisation. Scholars may fruitfully turn their attention, in this context, to his works The Human Cycle, The Ideal of Human Unity, and War and Self-Determination.

Sri Aurobindo’s views on internationalism, in contrast to the presently dominant and hegemonic ‘global modern’ that stands for the Americanisation of the world, would appeal to the modern academic world rooted in a liberal culture and thinking. They would be found instructive to civic planners in the domain of multicultural education, envisioned by thinkers like Charles Taylor and Anthony Appiah.17 The latter advocates the need and possibilities of maintaining a pluralistic culture of many identities and sub-cultures while retaining the civil and political practices that sustain natural life in the classic sense.

Such a view finds powerful echoes in Sri Aurobindo.18

As Sri Aurobindo writes:

But uniformity is not the law of life. Life exists by diversity; it insists that each group, every being shall be, even while one with all the rest in its universality, yet by some principle or ordered detail of variation unique.…Order is indeed the law of life, but not an artificial regulation.

The sound order is that which comes from within as the result of a nature that has discovered itself and found its own law and the law of its relation with others. Therefore the truest order is that which is founded on the greatest possible liberty; for liberty is at once the condition of vigorous variation and the condition of self-finding.

~ CWSA, Vol. 25, p. 513

Integral Education

Sri Aurobindo’s progressive and futuristic views on education and the aim of life have found powerful resonance in the domain of contemporary teacher-training institutes and centres for alternative education19 in India. His views on the theory and practice of an integral education find reflection in India’s New Education Policy 2020.

Child-centred learning, the need to free students, across the board, from bondages to textbooks and examinations, for the sake of holistic education, these are now an article of faith at the National Council of Educational Research and Teaching [NCERT] and other centres of teacher education.

Click HERE for Education related articles on Renaissance

Sri Aurobindo and Consciousness Studies

As in the case of International Relations, Global Studies, and the study of contemporary multiculturalism, discerning scholars in India and abroad today, are silently carrying out research in the field of Yoga psychology and consciousness studies, following the leads given by Sri Aurobindo.

The pioneer in this field was clearly Prof Indra Sen20 who shared close professional ties with his counterparts in India and abroad. Aligned to an interest in Indic Studies and the study of the indigenous knowledge systems, the subject is being avidly researched in institutes such as the California Institute of Integral Studies in the United States and the Indian Psychology Institute in India.21

Final Thoughts

University systems in the East and the West have served their mission well and are destined to do so in future. It is too early to write an epitaph for the Liberal Arts University.

The newer views of life, literature, and society that have emerged in recent years in academia may find echoes in the prophetic writings of Sri Aurobindo. For him, the matter-spirit binary, the empirical and spiritual divide, has been a great stumbling block for the betterment of the planetary world.

I have underlined in this essay some of the key ideas of Sri Aurobindo that could be taken forward for further treatment in academia, both present and future. All the same, a fundamental question remains:

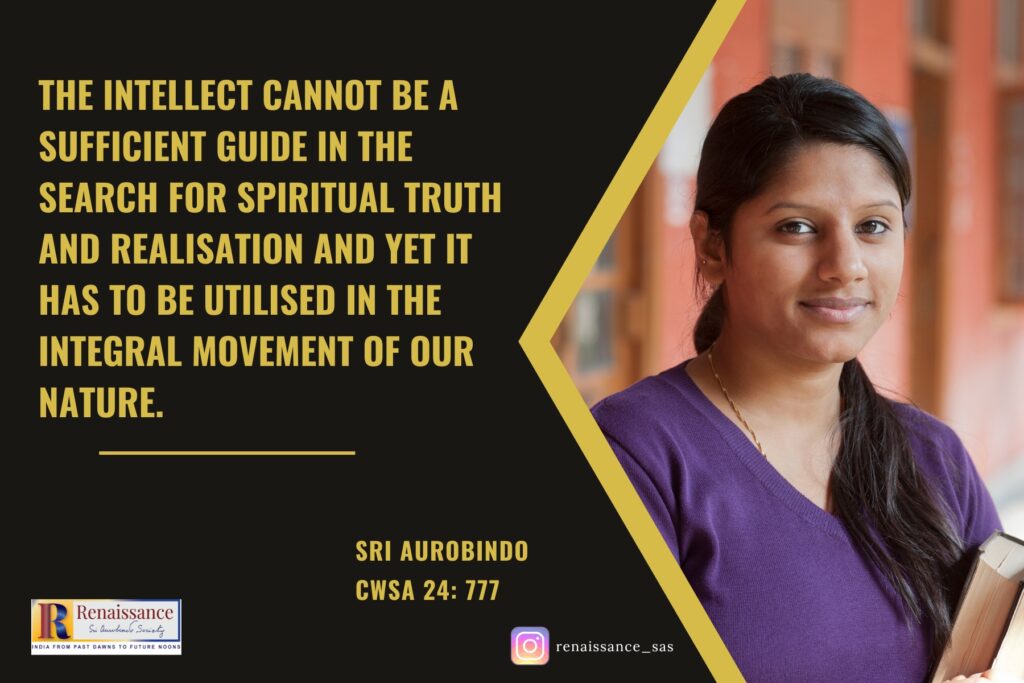

Why should a yogic consciousness bother about the rational mind that is at the heart of university education?

Sri Aurobindo, we may recall, devotes an entire chapter to ‘The Office and Limitations of the Reason’ in The Human Cycle. In The Synthesis of Yoga, he draws our attention pointedly to the ‘seeking intelligence’, while showing us the place of the intellect in spiritual life.22 In this explanation, we may discover a larger truth, namely, the raison d’être of the modern university.

As Sri Aurobindo says:

The intellect cannot be a sufficient guide in the search for spiritual truth and realisation and yet it has to be utilised in the integral movement of our nature.

And while, therefore, we have to reject paralysing doubt or mere intellectual scepticism, the seeking intelligence has to be trained to admit a certain large questioning an intellectual rectitude not satisfied with half-truths, mixtures of error or approximation and, most positive and helpful, a perfect readiness always to move forward from truths already held and accepted to the greater corrective, completing or transcending truths which at first it was unable or, it may be, disinclined to envisage.

~ CWSA, Vol. 24, p. 777

Right from his Cambridge days through the Bengal, Baroda, and Pondicherry phases, Sri Aurobindo evinced a keen interest in the development of the university system. He was deeply concerned about the ‘thought phobia’ that afflicted the Indian nation, as he wrote with concern to his younger brother Barin.

Sri Aurobindo was not drawn to pedantry, or an arid scholarship that was not related to life. At Baroda and Bengal, he disfavoured the soul-killing rote learning that destroyed originality and creativity in learners.

The Mother founded the Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education (SAICE) on his principles. Sri Aurobindo wrote extensively on national education, an education that is progressive and futuristic in character that could take the nation forward in a national resurgence and towards a greater future. It is time the nation heeded his message.

Read more by the author in Renaissance

Sri Aurobindo and India of the Future

CLICK: Sri Aurobindo Society signs MoU with Pondicherry University

Notes and References

- James Cousins, New Ways in English Literature (Madras: Ganesh and Co., 1917). ↩︎

- See Gautam Malaker, ‘Sri Aurobindo and the Nobel Prize’ for a fuller treatment of the subject, Mother India, Vol. LXXVI, No 1, January, 2023, pp.82–92. ↩︎

- Ibid, pp.84–86. ↩︎

- Quoted in K.D. Verma, ‘Sri Aurobindo as a Critic’, The Indian Imagination (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, https://rb.gy/3q6u5. See the various anthologies of Indian English poetry edited by Makarand Paranjape for a sympathetic approach and the study of Sri Aurobindo’s literary work especially in the context of Tagore by Goutam Ghoshal, formerly with Visva Bharati University, Santiniketan. ↩︎

- See Sri Aurobindo, Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest, The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo (CWSA), Vol. 36, pp. 504–05 (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department, 2006). ↩︎

- See the work of Peter Heehs on Sri Aurobindo in the context of modern Indian history. Similarly, the study of Indian history in the light of Sri Aurobindo, by Kittu Reddy in several volumes with a nationalistic perspective, would be of interest to scholars in the field. See the earlier pioneering work in the domain of Social Sciences and related disciplines by Kishor Gandhi, Sanat K. Banerjee, Sisir Kumar Mitra and others. ↩︎

- See K.D. Sethna, Ancient India in a New Light (New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, 1997); Sethna, The Problems of Ancient India (New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, 2000). Also see, K.D. Sethna: A Centenary Tribute, Ed. Sachidananda Mohanty (USA: The Integral Life Foundation, 2004). ↩︎

- See, in particular, Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukerji’s address at the convention to inaugurate the Sri Aurobindo University Centre at Pondicherry in 1951 as well as the address of Dr. Karan Singh in the Indian Parliament in connection with the passing of the Auroville Foundation Act. See also Dr. Karan Singh’s book The Prophet of Indian Nationalism. ↩︎

- See M.P. Pandit’s writings on Sri Aurobindo and the Vedas and the pioneering work by Kapali Shastri. In recent years, Debashish Banerji of the California Institute of Integral Studies and his team have carried out research on Sri Aurobindo, especially on the ancient Indian texts. ↩︎

- See Arvind Krishna Mehrotra: https://rb.gy/7fizq ↩︎

- For a fuller treatment of this subject, one may refer to Debapriya Goswami, ‘Aurobindonean Rhetoric and the Problem of Evaluation’, The Criterion: An International Journal in English, Vol. 8, Issue II, April 2017. ↩︎

- See K.D. Verma, ‘Sri Aurobindo as a Critic’, The Indian Imagination: https://rb.gy/vzu3a ↩︎

- C. D. Narasimhaiah, ‘Aurobindo: Inaugurator of Modern Indian Criticism,’ Journal of South Asian Literature, Vol. 24, No.1, Winter-Spring, 1989, pp. 87–103, published by the Asian Studies Centre, Michigan State University. ↩︎

- See Fredric Jameson, The Cultural Turns: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983–1998 (Brooklyn: Verso, 1998). ↩︎

- See Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine, CWSA Vol.21, pp. 66–77 (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department, 2005) ↩︎

- Ibid, Vol. 22, pp. 659-682. ↩︎

- See Sachidananda Mohanty, Cosmopolitan Modernity in Early 20th Century India, Revised 2nd, (South Asia and Global editions, 2018); Sachidananda Mohanty, Ed. Sri Aurobindo: A Contemporary Reader (New Delhi: Routledge, 2009, South Asia edition, 2016). ↩︎

- Sri Aurobindo, The Ideal of Human Unity, CWSA Vol. 25, pp. 243–44 (Pondicherry; Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department, 1998) ↩︎

- See the works of Ameeta Mehra and team at the Gnostic Centre New Delhi and more importantly, the pivotal experiments carried out at the SAICE, Pondicherry, Sri Aurobindo Society, Sri Aurobindo Ashram—Delhi Branch, and at SAIER, Auroville over half a century. ↩︎

- See Haridas Chaudhuri, (1975). “Psychology: Humanistic and Transpersonal”, Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 15 (1), 7-15; Haridas Chaudhuri, The Evolution of Integral Consciousness (Wheaton, Illinois: Quest Books, 1988); Indra Sen, Integral Psychology: The Psychological System of Sri Aurobindo (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education 2020); Shirazi, Bahman (2001) “Integral psychology, metaphors and processes of personal integration”, Matthijs Cornelissen (Ed.) Consciousness and Its Transformation, (Pondicherry: SAICE) [online] ↩︎

- Similarly, A.S. Dalal, Kireet Joshi, Matthijs Cornelissen and their students have carried out valuable research on Sri Aurobindo in the context of Indian psychology. See also Kireet Joshi Archives: Sri Aurobindo and Integral Yoga Psychology. Likewise, Arindam Basu, Madhusudan Reddy, M.V. Nadkarni, Aster Patel, and in more recent years, R.C. Pradhan, Ananda Reddy (SACAR), Alok Pandey and others have written on the philosophy of Sri Aurobindo at the wider level. ↩︎

- Sri Aurobindo, The Synthesis of Yoga, CWSA Vols. 23–24, pp.778–79 (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department, 1999) ↩︎

About the Author:

Sachidananda Mohanty, Ph.D., was formerly Professor and Head, Department of English, University of Hyderabad, and Vice-Chancellor of the Central University of Odisha. He also served as Governing Board Member of Auroville Foundation, Government of India. He was a Member of India’s Commission of Education to the UNESCO, Consultant to the Ford Foundation, and Senior Academic Associate at the American Studies Research Centre, [ASRC], Hyderabad.

Dr. Mohanty was educated at Bhubaneswar, Pondicherry, [Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education], the University of Hyderabad, IIT Kanpur, Nottingham University, University of Texas at Austin, and Yale University, New Haven. He has published more than 100 research articles and 28 books in English and Odia. Recipient of many coveted national and international awards, he is also a widely respected public intellectual and an active voice in several leading forums.