Volume V, Issue 11-12

Author: Ananda Coomaraswamy

Editor’s Note: Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy is a familiar name for every student or rasika of Indian Art. He is widely acknowledged as one of the great art historians and scholars of Indian art. Coomaraswamy was an early interpreter of Indian culture to the West. His numerous writings cover areas such as visual arts, aesthetics, literature and language, folklore, mythology, religion, and metaphysics. One of his most significant contributions was in the study of the language of symbolism contained in images.

We serialize a comprehensive essay on Indian Art by Ananda Coomaraswamy. It will be presented in 5 parts over the next several months, with first 2 parts in this issue. This essay was first published in 1908 by the Essex House Press in a limited edition. For the purpose of virtual reading, we have made a few minor formatting revisions.

Source: Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Winter, 1975). © World Wisdom, Inc.

www.studiesincomparativereligion.com

PART 1

The extant remains of Indian art cover a period of more than two thousand years. During this time many schools of thought have flourished and decayed, invaders of many races have poured into India and contributed to the infinite variety of her intellectual resources; countless dynasties have ruled and passed away; and so we do not wonder that many varieties of artistic expression remain, to record for us, in a language of their own, something of the ideas and the ideals of many peoples, their hopes and fears, their faith and their desire.

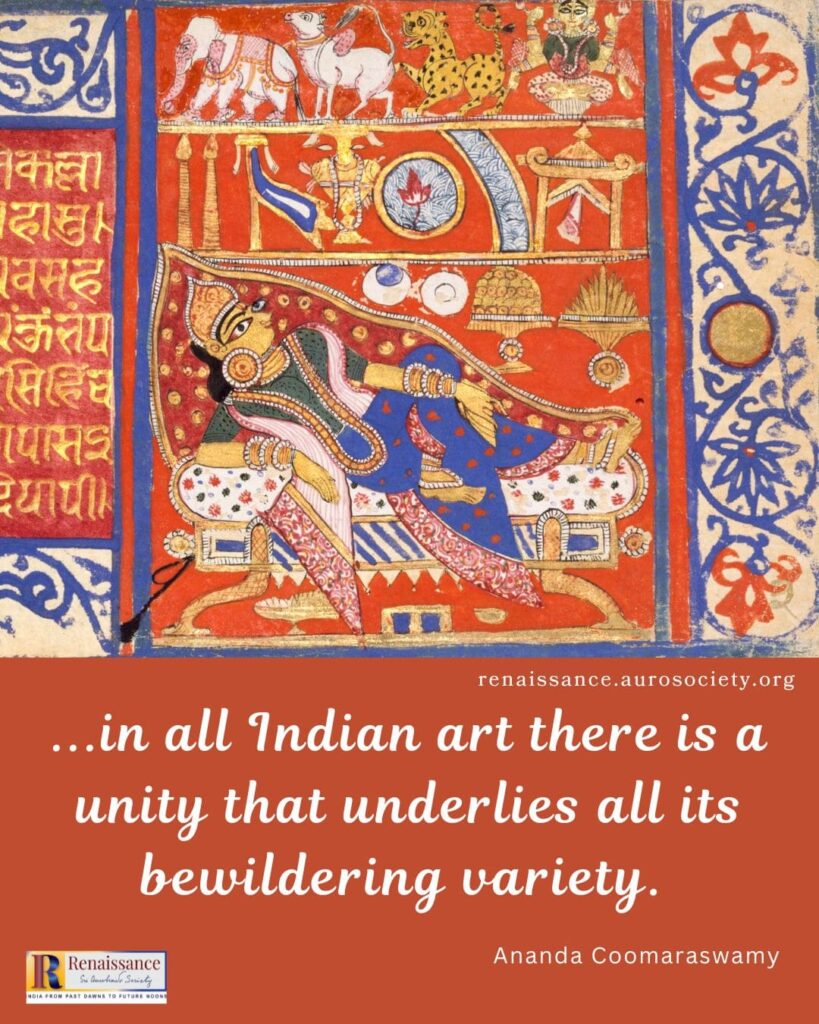

But just as through all Indian schools of thought there runs like a golden thread the fundamental idealism of the Upanishads, the Vedanta, so in all Indian art there is a unity that underlies all its bewildering variety. This unifying principle is here also Idealism, and this must of necessity have been so, for the synthesis of Indian thought is one, not many.

What, after all, is the secret of Indian greatness?

Not a dogma nor a book; but the great open secret that all knowledge and all truth are absolute and infinite, waiting not to be created, but to be found the secret of the infinite superiority of intuition, the method of direct perception, over the intellect, regarded as a mere organ of discrimination.

There is about us a storehouse of the As-Yet-Unknown, infinite and inexhaustible; but to this wisdom, the way of access is not through intellectual activity. The intuition that reaches to it we call Imagination and Genius. It came to Sir Isaac Newton when he saw the apple fall, and there flashed across his brain the Law of Gravity.

It came to the Buddha as he sat through the silent night in meditation. And hour by hour all things became apparent to him. He knew the exact circumstances of all beings that have ever been in the endless and infinite worlds. At the twentieth hour he received the divine insight by which he saw all things within the space of the infinite sakvalas as clearly as if they were close at hand. Then came still deeper insight. And he perceived the cause of sorrow and the path of knowledge. “He reached at last the exhaustless source of truth”.

The same is true of all “revelation”; the Veda (sruti), the eternal Logos, “breathed forth by Brahman”, in whom it survives the destruction and creation of the Universe, is “seen”, or “heard”, not made, by its human authors… The reality of such perception is witnessed to by every man within himself upon rare occasions and on an infinitely smaller scale. It is the inspiration of the poet. It is at once the vision of the artist, and the imagination of the natural philosopher.

Art and Science

There is a close analogy between the aims of art and of science. Descriptive science is, of course, concerned only with the record of appearances; but art and theoretical science have much in common. The imagination is required for both. Both illustrate that natural tendency to seek the one in the many, to formulate natural laws, which is expressed in the saying that the human mind functions naturally towards unity.

The aim of the trained scientific or artistic imagination is to conceive (concipio, lay hold of), invent (invenio, to light upon) or imagine (visualise) some unifying truth previously unsuspected or forgotten. The theory of evolution or of electrons or atoms; the rapid discovery (un-veiling) by a mathematical genius of the answer to an abtruse calculation; the conception that flashes into the artist’s mind, all these represent some true vision of the Idea underlying phenomenal experience, some message from the “exhaustless source of truth”.

Ideal art is thus rather a spiritual discovery than a creation. It differs from science in its concern primarily with subjective things, things as they are for us, rather than in themselves. But both art and science have the common aim of unity; of formulating natural laws.

Mental Images

It is said of a certain famous craftsman that when designing, he seemed not to be making, but merely to be outlining a pattern that he already saw upon the paper before him. The true artist does not think out his picture, but “sees” it; his desire is to represent his vision in the material terms of line and colour. To the great painter, such pictures come continually, often too rapidly and too confusedly to be caught and disentangled.

Could he but control his mental vision, define and hold it! But “fickle is the mind, forward, forceful, and stiff: I deem it as hard to check as is the wind”; yet by “constant labour and passionlessness it may be held”. And this concentration of mental vision has been from long ago the very method of Indian religion. And the control of thought its ideal of worship.

It is thus that the Hindu worships daily his Ishta Devatā, the special aspect of divinity that is to him all and more than the Patron Saint is to the Catholic. Simple men may worship such an one as Ganesha, easy to reach, not far away. Some can make the greater effort needed to reach even Natarāja. And only for those whose heart is set upon the Unconditioned, is a mental image useless as a centre of thought. These last are few.

Read:

Soul-realisation: The Method of Artistic Creation

For those that adore an Ishta Devatā, or conditioned and special aspect of God, worship of Him consists first in the recitation of the brief mnemonic mantram detailing His attributes. Then in silent concentration of thought upon the corresponding mental image. These mental images are of the same nature as those the artist sees. And the process of visualisation is the same. Here, for example, is a verse from one of the imager’s technical books (the Rupāvaliya):

These are marks of Siva: a glorious visage, three eyes, a bow and an arrow, a serpent garland, ear-flowers, a rosary, four hands, a trisūla, a noose, a deer, bands betokening mildness and beneficence, a garment of tiger skin, His vāhan a bull of the hue of the chank.1

It may be compared with the Dhyāna mantrams used in the daily meditation of a Hindu upon the Gayatri visualised as a Goddess:

In the evening Sarasvati should be meditated upon as the essence of the Sāma Veda, fair of face, having two arms, holding a trisūla and a drum, old; and as Rudrani, the bull her vāhan.

Almost the whole philosophy of Indian art is contained in the verse of Sukrācârya’s Sukranitisāra which enjoins this method of visualisation upon the imager:

In order that the form of an image may be brought fully and clearly before the mind, the image maker should meditate; and his success will be in proportion to his meditation. No other way—not indeed seeing the object itself—will achieve his purpose.2

Maya

It cannot be too clearly understood that the mere representation of nature is never the aim of Indian art. Probably no truly Indian sculpture has been wrought from a living model, or any religious painting copied from life. Possibly no Hindu artist of the old schools ever drew from nature at all. His store of memory pictures, his power of visualisation and his imagination were, for his purpose, finer means. For he desired to suggest the Idea behind sensuous appearance, not to give the detail of the seeming reality, that was in truth but māyā, illusion.

For in spite of the pantheistic accommodation of infinite truth to the capacity of finite minds, whereby God is conceived as entering into all things, Nature remains to the Hindu a veil, not a revelation. And art is to be something more than a mere imitation of this māyā. It is to manifest what lies behind. To mistake the māyā for reality were error indeed:

Men of no understanding think of Me, the unmanifest, as having manifestation, knowing not My higher being to be changeless, supreme.

Bhagavad Gitā, VII , 24, 25

Veiled by the Magic of My Rule (Yoga-Māyā), I am not revealed to all the world; this world is bewildered, and perceives Me not as birthless and unchanging.

Indo-Persian

Of course, an exception to these principles in Indian art may be pointed to in the Indo-Persian school of portrait miniature. And this work does show that it was no lack of power that in most other cases kept the Indian artist from realistic representation. But here the deliberate aim is portraiture, not the representation of Divinity or Superman. And even in the portraits there are many ideal qualities apparent.

In purely Hindu and religious art, however, even portraits are felt to be lesser art than the purely ideal and abstract representations. Such realism as we find, for example, in the Ajanta paintings, is due to the keenness of the artist’s memory of familiar things, not to his desire faithfully to record appearances. For realism that thus represents keenness of memory picture, strength of imagination, there is room in all art; duly restrained, it is so much added power. But realism which is of the nature of imitation of an object actually seen at the time of painting is quite antipathetic to imagination. It finds no place in the ideal of Indian art.

Truth to Nature

Much of the criticism applied to works of art in modern times is based upon the idea of “truth to nature”. The first thing for which many people look in a work of art is for something to recognize. And if the representation is of something they have not seen, or symbolizes some unfamiliar abstract idea, it is thereby self-condemned as untrue to nature.

What, after all, is reality and what is truth? The Indian thinker answers that nature, the phenomenal world that is, is known to him only through sensation. And that he has no warrant for supposing that sensations convey to him any adequate conception of the intrinsic reality of things in themselves. Nay, he denies that they have any such reality apart from himself. At most, natural forms are but incarnations of ideas, and each is but an incomplete expression. It is for the artist to portray the ideal world (Rūpa-loka) of true reality, the world of imagination; and this very word imagination, or visualisation, expresses the method he must employ.

How strangely this art philosophy contrasts with that characteristic of the modern West, so clearly set forth in Browning’s poem:

But why not do as well as say,—paint these

Just as they are, careless what comes of it?

God’s works—paint any one…

…Have you noticed, now,

Yon cullion’s hanging face? A bit of chalk,

And trust me but you should though! How much more

If I drew higher things with the same truth!

That were to take the Prior’s pulpit-place,

Interpret God to all of you!

For such realists, this last is not the function of art; but to us it seems that the very essential function of art is to “interpret God to all of you”.

Notes

- i.e., riding upon a snow-white bull. ↩︎

- In other words: “The artist should attain to the images of Gods by means of spiritual contemplation only. This spiritual vision is the best and truest standard for him. He should depend upon it ; and not, indeed, upon the visible objects perceived by the external senses”. ↩︎

Continued in Part 2

~ Design: Beloo Mehra