Volume V, Issue 11-12

Authors: Ananda Coomaraswamy

Source: Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Winter, 1975). © World Wisdom, Inc.

www.studiesincomparativereligion.com

Continued from PART 1

Burne-Jones

Burne-Jones almost alone amongst artists of the modern West seems to have understood art as we in India understand it. To a critic who named as a drawback in the work of a certain artist, that his pictures looked as if he had done them only out of his head, Burne-Jones replied, “The place where I think pictures ought to come from”.

Of impressionism as understood in the West, and the claim that breadth is gained by lack of finish, Burne-Jones spoke as an Eastern artist might have done. Breadth could be got “by beautiful finish and bright, clear colour well-matched, rather than by muzzy. They [the Impressionists] do make atmosphere, but they don’t make anything else. They don’t make beauty, they don’t make design, they don’t make idea, they don’t make anything but atmosphere—and I don’t think that’s enough—I don’t think it’s very much”.

Of realism he spoke thus:

“Realism? Direct transcript from Nature? I suppose by the time the “photographic artist” can give us all the colours as correctly as the shapes, people will begin to find out that the realism they talk about isn’t art at all, but science; interesting, no doubt, as a scientific achievement, but nothing more ….

“Transcripts from Nature, what do I want with transcripts? I prefer her own signature; I don’t want forgeries more or less skilful…. It is the message, the “burden” of a picture that makes its real value”.

At another time he said, “You see, it is these things of the soul that are real—the only real things in the universe”.

Of the religiousness of art, he said:

That was an awful thought of Ruskin’s, that artists paint God for the world. There’s a lump of greasy pigment at the end of Michaelangelo’s hog-bristle brush, and by the time it has been laid on the stucco, there is something there that all men with eyes recognize as divine. Think of what it means. It is the power of bringing God into the world—making God manifest.

The object of art must be either to please or to exalt: I can’t see any other reason for it at all. One is a pretty reason, the other a noble one.

Of “expression” in imaginative pictures, he said:

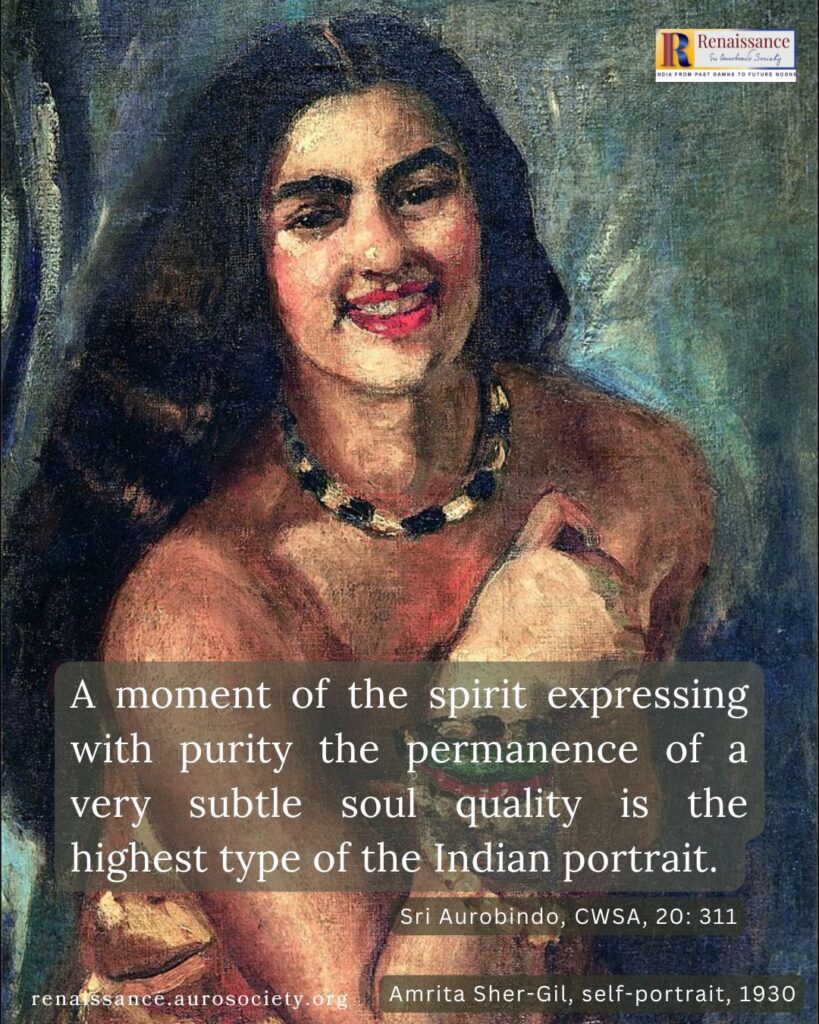

“Of course my faces have no expression in the sense in which people use the word. How should they have any? They are not portraits of people in paroxysms—paroxysms of terror, hatred, benevolence, desire, avarice, veneration and all the “passions” and “emotions” that Le Brun and that kind of person find so magnifique in Raphael’s later work . . .

“The only expression allowable in great portraiture is the expression of character and moral quality, not of anything temporary, fleeting, accidental. Apart from portraiture you don’t want even so much, or very seldom: in fact you want only types, symbols, suggestions. The moment you give what people call expression, you destroy the typical characters of heads and degrade them into portraits which stand for nothing”.1

Technical Perfection

Common criticisms of Indian art are based on supposed or real limitations of technical attainment in representations, especially of the figure. In part, it may be answered that so little is known in the West of the real achievement of Indian art, that this idea may be allowed to die a natural death in the course of time. And in part, that technical attainment is only a means, not an end.

There is an order of importance in the things art means to us. Is it not something thus: first, What has the artist to say? and second only, Is his drawing scientifically accurate? Bad drawing is certainly not in itself desirable, nor good drawing, a misfortune. But, strange as it may seem, it has always happened in the history of art that by the time perfection of technique has been attained, inspiration has declined.

It was so in Greece, and in Europe after the Renaissance. It almost seems as if concentration upon technique hindered the free working of the imagination a little; if so, however much we desire both, do not let us make any mistake as to which is first.

Also, accuracy is not always even desirable. It has been shown by photography that the galloping horse has never been accurately drawn in art; let us hope it never will be. For art has to make use of abstractions and memory pictures, not of photographs; it is a synthesis, not an analysis. And so the whole question of accuracy is relative. The last word was said by Leonardo da Vinci:

“That figure is best which by its action best expresses the passion that animates it”.

This is the true impressionism of the East, a very different thing from impressionism as now understood in the West.

Indian Art Religious

Indian art is essentially religious. The conscious aim of Indian art is the portrayal of Divinity. But the infinite and unconditioned cannot be expressed in finite terms. And art, unable to portray Divinity unconditioned, and unwilling to be limited by the limitation of humanity, is in India dedicated to the representation of Gods, who, to finite man, represent comprehensible aspects of an infinite whole.

Shankarācārya prayed thus:

“O Lord, pardon my three sins: I have in contemplation clothed in form Thyself that hast no form; I have in praise described Thee who dost transcend all qualities; and in visiting shrines I have ignored Thine omnipresence.”

So, too, the Tamil poetess Auwai was once rebuked by a priest for irreverence, in stretching out her limbs towards an image of God. “You say well, Sir,” she answered, “yet if you will point out to me a direction where God is not, I will there stretch out my limbs.”

But such conceptions, though we know them at heart to be true and absolute, involve a denial of all exoteric truth. They are not enough, or rather they are too much, for ordinary men to live by:

Exceeding great is the toil of these whose mind is attached to the Unshown; for the Unshown Way is painfully won by them that wear the body.

But as for them who, having cast all works on Me and given themselves over to Me, worship Me in meditation, with whole hearted yoga

These speedily I lift up from the sea of death and life, O Pārtha, their minds being set on Me.

Bhagavad Gitā, XII, 5-7

And so it is that “any Indian man or woman will worship at the feet of some inspired wayfarer who tells them that there can be no image of God, that the world itself is a limitation, and go straight-way, as the natural consequence, to pour water on the head of the Siva-lingam”.2 Indian religion has accepted art, as it has accepted life in its entirety, with open eyes.

Read:

The Relation of Art to Yoga

India, with all her passion for renunciation, has never suffered from that terrible blight of the imagination which confuses the ideals of the ascetic and of the citizen. The citizen is indeed to be restrained. But the very essence of his method is that he should learn restraint or temperance by life not by the rejection of life. For him, the rejection of life, called Puritanism, would be in-temperance.

Renunciation

What then of the true ascetic, with his ideal of renunciation? It has been thought by many Hindus and Buddhists, as it has by many Christians, that rapid spiritual progress is compatible only with an ascetic life. The goal before us all is salvation from the limitation of individuality, and realisation of unity with unconditioned absolute being. Before such a goal can be attained, even the highest intellectual and emotional attachments must be put away; art, like all else in time and space, must be transcended.

Three states or planes of existence are spoken of in Indian metaphysics: Kāma-loka, the sphere of phenomenal appearance; Rūpa-loka, the sphere of ideal form; and Arūpa-loka, the sphere beyond form. Great art suggests the ideal forms of the Rūpa-loka, in terms of the appearances of Kāma-loka.

But what is art to one that toils upon the Unshown Way, seeking to transcend all limitations of the human intellect, to reach a plane of being unconditioned even by ideal form? For such an one, the most refined and intellectual delights are but flowery meadows where men may linger and delay, while the strait path to utter truth waits vainly for the traveller’s feet.

READ:

The Different Paths of an Artist and a Sadhu

This thought explains the belief that absolute emancipation is hardly won by any but human beings yet incarnate. It is harder for the gods to attain such release, for their pure and exalted bliss and knowledge are attachments even stronger than these of earth. And so we find such an instruction as this:

Form, sound, taste, smell, touch, these intoxicate beings; cut off the yearning which is inherent in them (Dhammika Sutta).

The extreme expressions of this thought seem to us more terrible than even the “coldness of Christian men to external beauty”. We feel this, for instance, in reading the story of the Buddhist monk, Chitta Gutta, who dwelt in a certain cave for sixty years without ever raising his eyes above the ground so far as to observe the beautifully painted roof. Not was he ever aware of the yearly flowering of a great na-tree before his cave, except through seeing the pollen fallen upon the ground.

But Indian thought has never dreamed of imposing such ideals upon the citizen, whose dharma lies, not in the renunciation of action, but in right action without attachment to its fruits. And for such, who must ever form the great majority of the people, art is both an aid to, and a means of, spiritual progress.

One thing is of importance for us.

While we run no risk of confusing these two ideals, we should not judge of their relative value or rightness for others. Each man must do that for himself. And so we are to respect both monk and citizen, peasant and king, not for their position, but for their fulfilment of their own ideals.

This same-sightedness explains to us the seeming paradox that Hinduism and Buddhism, with their ideals of renunciation, have, like Mediaeval Christianity, been at once the inspiration and the stronghold of art.

Notes

- Quotations from Memorial of Edward Burne-Jones, by Lady Burne-Jones, 1904 ↩︎

- Okakura, Ideals of the East, p. 65 ↩︎

To be continued…

~ Design: Beloo Mehra