Volume VI, Issue 1

Authors: Ananda Coomaraswamy

Source: Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Winter, 1975). © World Wisdom, Inc.

www.studiesincomparativereligion.com

CONTINUED FROM PART 2

Symbolism

India is wont to suggest the eternal and inexpressible infinities in terms of sensuous beauty. The love of man for woman or for nature are one with his love for God. Nothing is common or unclean. All life is a sacrament, no part of it more so than another, and there is no part of it that may not symbolize eternal and infinite things. In this great same-sightedness, how great is the opportunity for art.

But in this religious art it must not be forgotten that life is not to be represented for its own sake, but for the sake of the Divine expressed in and through it. It is laid down:

“It is always commendable for the artist to draw the images of gods. To make human figures is wrong, or even unholy. Even a mishapen image of God is always better than an image of man, however beautiful” (Śukrāchārya).

The doctrine here so sternly stated means, in other words, that imitation and portraiture are lesser aims than the representation of ideal and symbolic forms. The aim of the highest art must always be the intimation of the Divinity behind all form, rather than the imitation of the form itself. One may, for instance, depict the sport of Krishna with the Gopis, but it must be in a spirit of religious idealism, not for the mere sake of the sensuous imagery itself.

The doctrine here so sternly stated means, in other words, that imitation and portraiture are lesser aims than the representation of ideal and symbolic forms. The aim of the highest art must always be the intimation of the Divinity behind all form, rather than the imitation of the form itself. One may, for instance, depict the sport of Krishna with the Gopis, but it must be in a spirit of religious idealism, not for the mere sake of the sensuous imagery itself.

In terms of European art, it would have been wrong for Giotto or Botticelli, who could give to the world an ideal conception of the Madonna, to have been content to portray obviously earthly persons posing as the Madonna, as was done in later times, when art had passed downwards from spiritual idealism to naturalism. So also Millais’ later work has a lower aim than his earlier. In India also, the work of Ravi Varma, whose gods and heroes are but men cast in a very common mould, is “unholy” compared with the ideal pictures of Tagore.

Formal Beauty

What is the ideal of beauty implicit in Indian art? It is a beauty of type, impersonal and aloof. It is not an ideal of varied individual beauty, but of one formalised and rhythmic. The canons insist again and again upon the Ideal as the only true beauty.

“An image whose limbs are made in accordance with the rules laid down in the shāstras is beautiful. Some, however, deem that which pleases the fancy to be beautiful; but proportions that differ from those given it the shāstras cannot delight the cultured” (Śukrāchārya).

The appeal of formalised ideal beauty is for the Indian mind always stronger than that of beauty associated with the accidental and unessential. The beauty of art, whether fictile or literary, is more compelling and deeper than that of nature herself. These pure ideas, thus disentangled from the web of circumstance by art, are less realised and so more suggestive than fact itself. This is the explanation of the passionate love of nature expressed in Indian art and literature, that is yet combined almost with indifference to the beauty, certainly to the ‘picturesqueness’, of nature herself.

An essential part of the ideal of beauty is restraint in representation.

“The hands and feet should be without veins. The (bones of) the wrist and ankle should not be shown” (Śukrāchārya).

Over-minuteness would be a sacrifice of breadth. It is not for the imager to spend his time in displaying his knowledge or his skill; for over-elaborated detail may destroy rather than heighten the beauty of the work. In the presence of the work of Michaelangelo, we can never forget how much anatomy he knows.

But this objection to the laborious realisation of parts of a work of art must not be confused with the pernicious doctrine of the excellence of unfinished work. Oriental art is essentially clear and defined; its mystery does not depend on vagueness.

Adherence to the proportions laid down in the shāstras is even inculcated by imprecations.

“If the measurements be out by even half an inch, the result will be loss of wealth, or death” (Śāriputra).

“One who knows amiss his craft… after his death will fall into hell and suffer” (Mayamataya).

In such phrases we seem to see the framers of the canon consciously endeavouring to secure the permanence of the tradition in future generations, and amongst ignorant or inferior craftsmen. We shall see later what has been the function of tradition in Indian art. It appears here as an extension in time of the idea of formal beauty and symbolism.

Beauty Not the Only Aim

But it is not necessary for all art to be beautiful, certainly not pretty. If art is ultimately to “interpret God to all of you”, it must be now beautiful, now terrible, but always with that living quality which transcends the limited conceptions of beauty and ugliness.

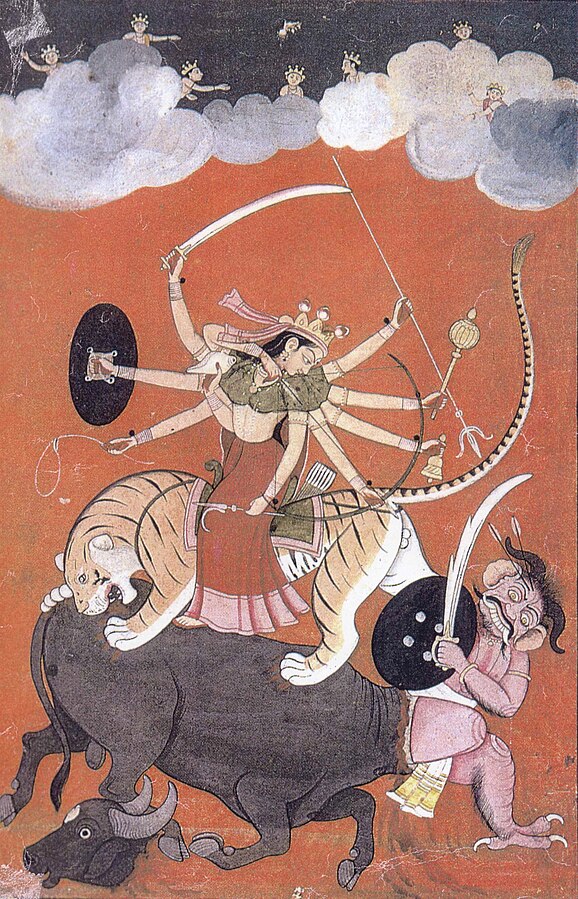

The personal God, whom alone art can interpret, is in and through all nature; “All this Universe is strung upon Me as gems upon a thread”. Nature is sometimes soft and smiling, sometimes also red in tooth and claw; in her, both life and death are found. Creation, preservation and destruction are equally His work. His images may therefore be beautiful or terrible.

In nature there are three gunas, or qualities, Sattva (truth), Rajas (passion), and Tamas (gloom). These qualities are always present in nature; their relative proportion determines the character of any particular subject or object. They must, therefore, enter into all material and conditioned representations, even of Divinity, in which, nevertheless, sattva guna must preponderate. And so we find a classification of images into three, sattvik, rajasik, and tamasik.

“An image of God, seated self-contained, in the posture of a yogi, with hands turned as if granting boon and encouragement to his worshippers, surrounded by praying and worshipping Indra and other gods, is called a sattvik image.

“An image seated on a vāhan, decked with various ornaments, with hands bearing weapons, as well as granting boon and encouragment, is called a rajasik image.

“A tamasik image is a terrible armed figure fighting and destroying the demons” (Śukrāchārya).

It is the same with architecture.

Here, too, the design is to suggest and symbolize the Universe. The site of a temple or town is laid out in relation to astrological observations. Every stone has its place in the cosmic design. And the very faults of execution represent but the imperfections and shortcomings of the craftsman himself.

Can we wonder that a beautiful and dignified architecture is thus devised, or can such conceptions fail to be reflected in the dignity and serenity of life itself? Under such conditions, the craftsman is not an individual expressing individual whims, but a part of the Universe giving expression to the ideals of its own eternal beauty and unchanging law.

Decorative Art

Exactly the same ideas of formal beauty prevail in relation to purely decorative art. The aim of such art is not, of course, in the same sense consciously religious. The simple expression of delight in cunning workmanship, or of the craftsman’s humour, or his fear or his desire are motifs that inspire the lesser art that belongs to the common things of life.

But yet all art is really one, consistent with itself and with life. How should one part of it be fundamentally opposed to another? And so we find in the decorative art of India the same idealism that is inseparable from Indian thought; for art, like religion, is really a way of looking at things, more than anything else.

The love of nature in its infinite beauty and variety has impelled the craftsman to decorate his handiwork with the forms of the well-known birds and flowers and beasts with which he is most intimate, or which have most appealed to his imagination. But these forms he never represents realistically. They are always memory pictures, combined with fanciful creations of the imagination into symmetrical and rhythmic ornament.

Pic: Virupaksha temple, Pattadakal (source)

Lions

Take, for example, the treatment of lions in decorative art. Verses of the canon relating to animals often show that the object of the canon has been as much to stimulate imagination, as to define the manner of representation.

“The neigh of a horse is like the sound of a storm, his eyes like the lotus, he is swift as the wind, as stately as a lion, and his gait is the gait of a dancer.

“The lion has eyes like those of a hare, a fierce aspect, soft hair long on his chest and under his shoulders, his back is plump like a sheep’s his body is that of a blooded horse, his gait is stately, and his tail long” (Śāriputra).

For comparison, I quote another description, from an old Chinese canon:

“With a form like that of a tiger, and with a colour tawny or sometimes blue, the lion is like the muku-inu,a shaggy dog. He has a huge head, hard as bronze, a long tail, forehead firm as iron, hooked fangs, eyes like bended bows, and raised ears; his eyes flash like lightning, and his roar is like thunder.”1

Such descriptions throw light on the representation of animals in Oriental decorative art. The artist’s lion need be like no lion on earth or in any zoological garden; for he is not illustrating a work on natural history. Freed from such a limitation, he is able to express through his lion the whole theory of his national existence and individual idiosyncracy.

Thus has Oriental art been preserved from such paltry and emasculated realism as that of the lions of Trafalgar Square. Contrast the absence of imagination in this handiwork of the English painter of domestic pets with the vitality of the heraldic lions of Mediaeval England, or the lions of Hokusai’s “Daily Exorcisms”.

The sculptured lions of Egypt, Assyria, or India are true works of art. For in them we see, not any lion that could today be shot or photographed in a desert, but the lion as he existed in the minds of a people, a lion that tells us something of the people who represented him.

In such artistic subjectivity lies the significance of Ancient and Eastern decorative art. It is this which gives so much dignity and value to the lesser arts of India, and separates them so entirely in spirit from the imitative decorative art of modern Europe.

To be continued…

READ

Part 1 Part 2

Notes

- Quoted in The Kokka, No. 198, 1906. ↩︎