Volume VI, Issue 2

Author: Ananda Coomaraswamy

Source: Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Winter, 1975). © World Wisdom, Inc.

www.studiesincomparativereligion.com

CONTINUED FROM PART 3

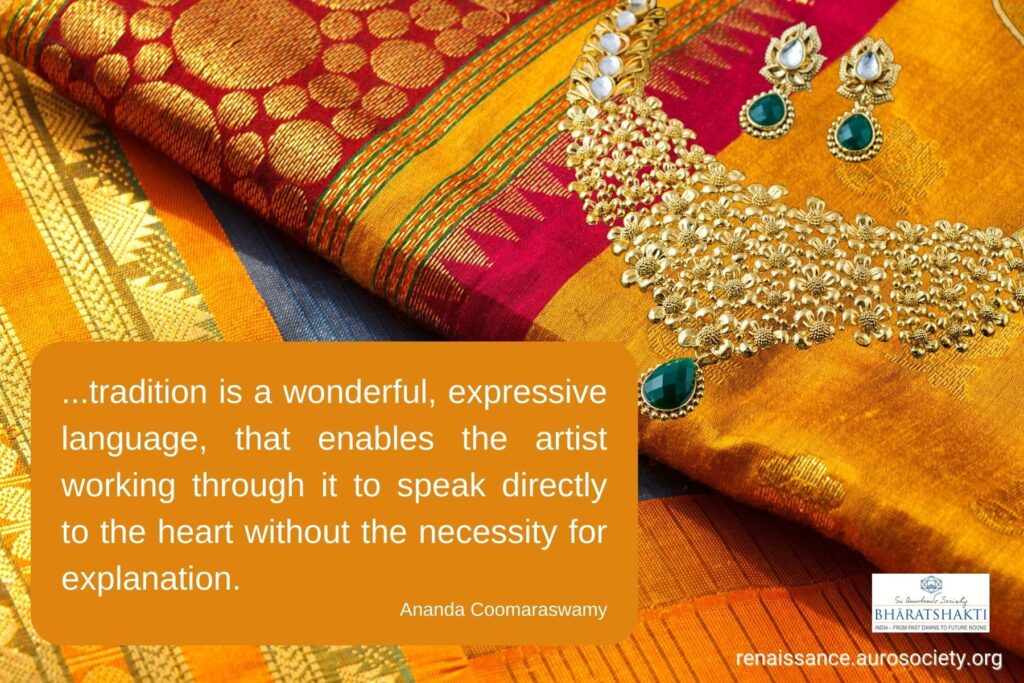

Jewellery

Take Indian jewellery as another illustration of idealism in decorative art. The traditional forms have distinctive names, just as a “curb bracelet” or a “gypsy ring” may be spoken of in England. In India the names are usually those of special flowers or fruits, or generic terms for flowers or seeds, as “rui-flower thread”, “coconut-flower garland,” “petal garland”, “string of millet grains”, “ear-flower”, “hair-flower”. These names are reminiscent of the garlands of real flowers, and the flowers in the hair that play so important a part in Indian festal dress. These, with the flowers and fruits worn as talismans or as religious symbols, are the prototypes of the flower forms of Indian jewellery, which thus, like all other Indian art, reflects the thought, the life and the history of the people by and for whom it is so beautifully made.

The traditional forms, then, are named after flowers; but it is highly characteristic that the garlands and flowers are in design purely suggestive, not at all imitative of the prototypes. The realism which is so characteristic of nearly all modern Western art, in jewellery producing the unimaginative imitations of flowers, leaves, and animals of the school of Lalique, is never found in Indian design.

Imitation and Design

The passion for imitation may be taken as direct evidence of the lack of true artistic impulse, which is always a desire, conscious or sub-conscious, to express or manifest Idea. Why indeed imitate where you can never rival? Nor is it by a conscious intellectual effort that a flower is to be conventionalised and made into applied ornament.

No true Indian craftsman sets a flower before him and worries out of it some sort of ornament by taking thought; his art is more deeply rooted in the national life than that. If the flower has not meant so much to him that he has already a clear memory picture of its essential characters, he may as well ignore it in his decoration; for a decorative art not intimately related to his own experience, and to that of his fellow men, could have no intrinsic vitality, nor meet with that immediate response which rewards the prophet speaking in a mother-tongue.

It is, of course, true that the original memory pictures are handed on as crystallised traditions; yet as long as the art is living, the tradition remains also plastic, and is moulded imperceptibly by successive generations. The force of its appeal is strengthened by the association of ideas—artistic, emotional and religious.

Traditional forms have thus a significance not merely foreign to any imitative art, but dependent on the fact that they represent race conceptions, rather than the ideas of one artist or of a single period. They are a vital expression of the race mind: to reject them, and expect great art to live on as before, would be to sever the roots of a forest tree and still look for flowers and fruit upon its branches.

Patterns

Consider, also, patterns. I have found that to most people patterns mean extremely little; they are things to be made and cast aside for new, only requiring to be pretty, perhaps only to be fashionable; whereas they are things which live and grow, and which no man can create, all he can do is to use them, and to let them grow.

Every real pattern has a long ancestry and a story to tell. For those that can read its language, even the most strictly decorative art has complex and symbolical associations that enhance a thousandfold the significance of its expression, as the complex associations that belong to words, enrich the measured web of spoken verse. This is not, of course, to suggest that such art has a didactic character, but only that it has some meaning and something to say; but if you do not want to listen, it is still a piece of decoration far better than some new thing that has “broken” with tradition and is “original”.

May Heaven preserve us from the decorative art of today that professes to be new and original. The truth is expressed by Ruskin in the following words:

“That virtue of originality that men so strain after is not newness (as they vainly think), it is only genuineness; it all depends on this single glorious faculty of getting to the spring of things and working out from that.”

Observe that here we have come back to the essentially Indian point of view, getting to the spring of things, and working out from that. You will get all the freshness and individuality you want if you do that. This is to be seen in the vigour and vitality of the designs of William Morris, compared with the work of designers who have deliberately striven to be original. Morris tried to do no more than recover the thread of a lost tradition and carry it on; and yet no one could mistake the work of Morris for that of any other man or any other century or country—and is that not originality enough?

Convention

Convention may be defined as the manner of artistic presentation, while tradition stands for a historic continuity in the use of such conventional methods of expression. Many have thought that convention and tradition are the foes of art, and deem the epithets “conventional and traditional” to be in themselves of the nature of destructive criticism.

Convention is conceived of solely as limitation, not as a language and a means of expression. But to one realising what tradition really means, a quite contrary view presents itself; that of the terrible and almost hopeless disadvantage from which art suffers when each artist and each craftsmen, or at the best, each little group and school, has first to create a language, before ideas can be expressed in it. For tradition is a wonderful, expressive language, that enables the artist working through it to speak directly to the heart without the necessity for explanation. It is a mother-tongue, every phrase of it rich with the countless shades of meaning read into it by the simple and the great that have made and used it in the past.

It may be said that these principles hold good only in relation to decorative art. Let us then enquire into the place and influence of tradition in the fine art of India. The written traditions, once orally transmitted, consist mainly of memory verses, exactly corresponding to the mnemonic verses of early Indian literature.

In both cases, the artist, imager or story-teller, had also a fuller and more living tradition, handed down in the schools from generation to generation, enabling him to fill out the meagre details of the written canon. Sometimes, in addition to the verses of the canon, books of mnemonic sketches were in use, and handed down from master to pupil in the same way. These give us an opportunity of more exactly understanding the nature and method of tradition.