Volume VI, Issue 3

Author: Ananda Coomaraswamy

Source: Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Winter, 1975). © World Wisdom, Inc.

www.studiesincomparativereligion.com

CONTINUED FROM PART 4

Nataraja

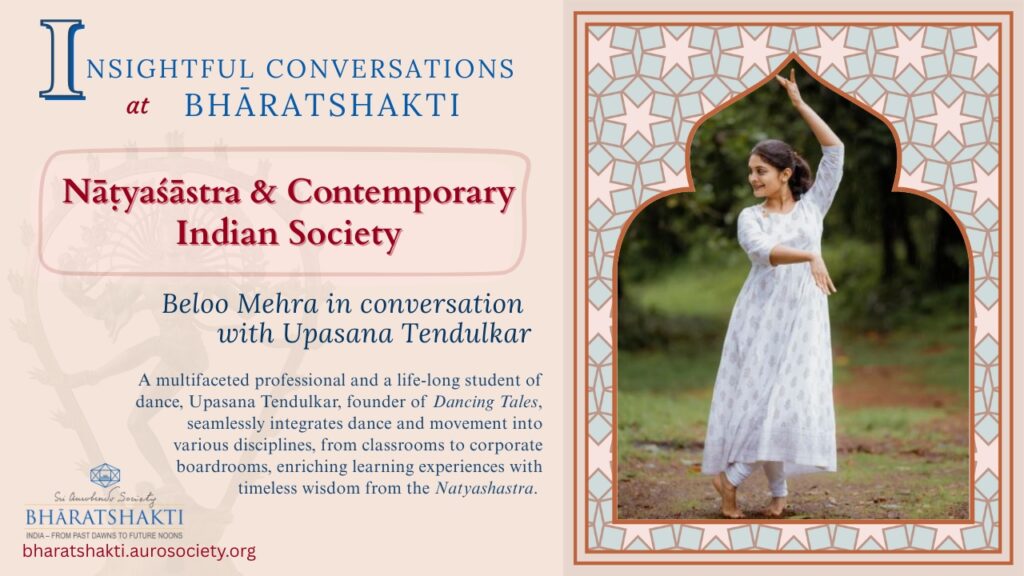

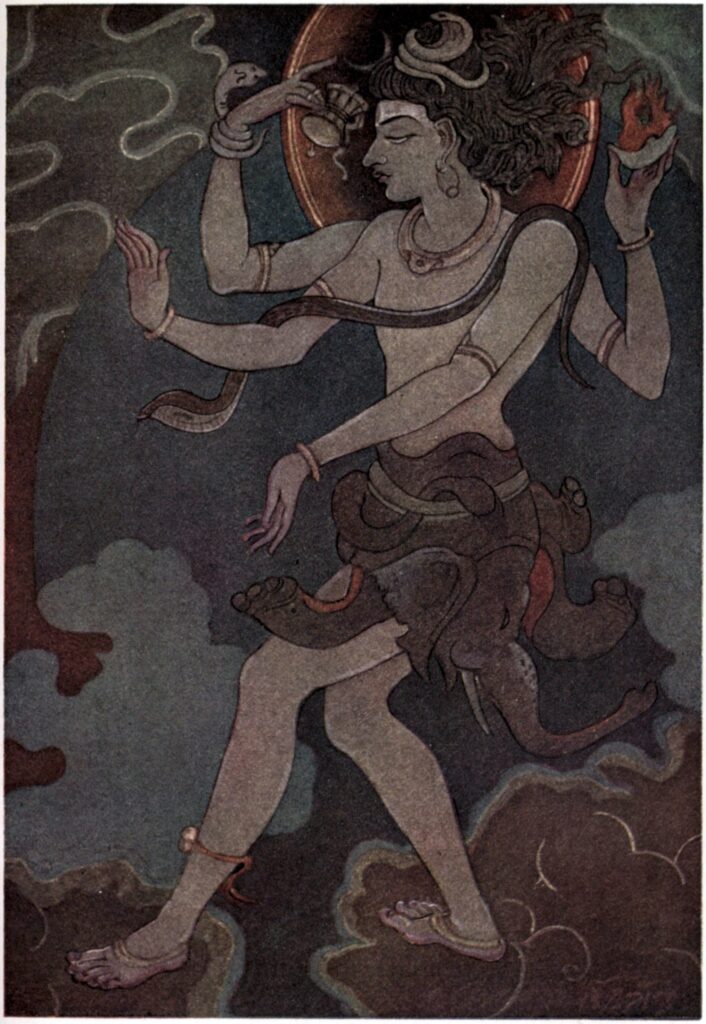

Pic 1: Nataraja: from a Tamil craftsman’s notebook (early XIX century)

The accompanying illustration is reproduced from an old Tamil craftsman’s sketch book, a figure of Siva as Nataraja. In order to understand this, it is necessary first to explain the legend and conception of Siva’s appearance as the “Dancing Lord”. The story is given in the Koyil Puranam, and is familiar to all Saivites.

Siva has appeared in disguise amongst a congregation of ten thousand sages and, in the course of disputation, confuted them and so angered them thereby, that they endeavoured by incantations to destroy Him. A fierce tiger was created in sacrificial flames, and rushed upon Him, but smiling gently, He seized it with His sacred hands, and with the nail of His little finger stripped off its skin, which He wrapped about Himself as if it had been a silken cloth.

Undiscouraged by failure, the sages renewed their offerings, and there was produced a monstrous serpent, which He seized and wreathed about His neck. Then He began to dance; but there rushed upon Him a last monster in the shape of a hideous malignant dwarf. Upon Him the God pressed the tip of His foot, and broke the creature’s back, so that it writhed upon the ground; and so, His last foe prostrate, Siva resumed the dance of which the gods were witnesses.

Interpreting the Story

One interpretation of this legend explains that He wraps about Him as a garment, the tiger fury of human passion; the guile and malice of mankind He wears as a necklace, and beneath His feet is for ever crushed the embodiment of evil. More characteristic of Indian thought is the symbolism, in terms of the marvellous grace and rhythm of Indian dancing, the effortless ease with which the God in His grace supports the cosmos; it is His sport.

The five acts of creation, preservation, destruction, embodiment and gracious release are His ceaseless mystic dance. In sacred Tillai, the “New Jerusalem”, the dance shall be revealed; and Tillai is the very centre of the Universe, that is, His dance is within the cosmos and the soul.1

Language of Its Own

The necessity for such an explanation emphasizes the apparent difficulty of understanding Indian art. But it must be remembered that the element of strangeness in Indian art is not there for its makers and those for whom they worked. It speaks, as all great national art must speak, in a language of its own, and it is evident that the grammar of this art language must be understood before the message can be appreciated, or the mind left free to consider what shall be its estimate of the artistic qualities of a work before it.

Here then is a rough sketch (pic 1), drawn by an inferior craftsman, and representing very fairly just that amount of guidance which tradition somewhat precisely hands on for the behoof of each succeeding generation of imagers. This conception is fairly often met with in Southern India, sculptured in stone or cast in bronze. Some of these representations have no especial artistic excellence; but so subjective is appreciation of art, so dependent on qualities belonging entirely to the beholder, and transferred by him into the object before him, that the symbolic and religious aim is still attained.

Functions of Tradition

Such is one of the functions of tradition, making it possible for ordinary craftsmen to work acceptably within its limits, and avoiding all danger of the great and sacred subjects being treated with loss of dignity or reverence. But tradition has another aspect, as enabling the great artist, the man of genius, to say in the language understood by the people, all that there is in him to express.

***

A bronze figure of Nataraja, perhaps of the seventeenth century or even older, is in the Madras Museum. It would be superfluous to praise in detail this beautiful figure; it is so alive, and yet so balanced, so powerful and yet so effortless. There is here realism for the realist, but realism that is due to keenness of memory for familiar things, not to their imitation.

The imager grew up under the shadow of a Sivan temple in one of the great cathedral cities of the South; perhaps Tanjore. He had worked with his father at the columns of the Thousand Pillared Hall at Madura. And later at the Choultry, when all the craftsmen of Southern India flocked to carry out the great buildings of Tirumala Nayaka.

Himself a Saivite, he knew all its familiar ritual, and day after day he had seen the dancing of the devadasis before the shrine, perhaps in his youth had been the lover of one more skilled and graceful than the rest; and all his memories of rhythmic dance, and mingled devotion for devadasi and for Deity, he expressed in the grace and beauty of this dancing Siva.

Art and Life

For so are religion and culture, life and art, bound up together in the web of Indian life. Is the tradition that links that art to life of little value, or less than none, to the great genius? Shall he reject the imagery ready to his hand, because it is not new and unfamiliar?

Look well at the figure, with its first and simplest motif of victory over evil; observe the ring of flaming fire, the aura of His glory; the four hands with the elaborate symbolism of their attitude; the fluttering angavastiram, and the serpent garland, and think whether any individual artist, creating his own convention and inventing newer symbolisms, could speak thus to the hearts of men, amongst whom the story of Siva’s dance is a gospel and a cradle tale.

Buddha

The seated Buddha is a more familiar type. Here, too, convention and tradition are held to fetter artistic imagination. Indian art is sometimes condemned for showing no development, because there is, or is supposed to be, no difference in artistic conception between a Buddha of the first century and one of the nineteenth.

It is, of course, not quite true that there is no development, in the sense that the work of each period is altogether uncharacterised, for those who know something of Indian art are able to estimate with some confidence the century to which a statue belongs. But it is true that the conception is really the same; the mistake lies in thinking this an artistic weakness.

The Indian Ideal

It is an expression of the fact that the Indian ideal has not changed. What is that ideal so passionately desired? It is one-pointedness, same-sightedness, control: little by little to control the fickle and unsteady mind; little by little to win stillness, to rein in, not merely the senses, but the mind, that is as hard to check as is the wind.

As a lamp that flickers not in a windless spot, so is the mind to be at rest. Only by constant labour and passionlessness is this peace to be attained. What is the attitude of mind and body of one that seeks it? He shall be seated like the image, for that posture, once acquired, is one of perfect bodily equipoise:

He shall seat himself with thought intent and the workings of mind and sense instruments restrained, for purification of spirit labour on the yoga.

Firm, holding body, head, and neck in unmoving equipoise, gazing on the end of his nose, and looking not round about him.

Calm of spirit, void of fear, abiding under the vow of chastity, with mind restrained and thought set on Me, so shall he sit that is under the Rule, given over unto Me.

In this wise the yogi … comes to the peace that ends in nirvana and that abides in Me

~ Bhagavad Gita, VI, 12-15

How then should the greatest of India’s teachers be represented in art? How otherwise than seated in this posture that is in the heart of India associated with every striving after the great Ideal, and in which the Buddha himself was seated on the night when the attacks of Mara were for ever foiled, and that insight came at last, to gain which the Buddha had in countless lives sacrificed his body “for the sake of creatures”? It was the greatest moment in India’s spiritual history; and as it lives in the race-memory, so is it of necessity presented in the race-art.

Conclusion

Such, then, have been the aims and method of Indian art in the past.

Two tendencies are manifested in the Indian art of today, the one inspired by the technical achievement of the modern West, the other by the spiritual idealism of the East. The former has swept away both the beauty and the limitation of the old tradition. The latter has but newly found expression; yet if the greatest art is always both national and religious (and how empty any other art must be), it is there alone that we see the beginnings of a new and greater art, that will fulfil and not destroy the past.

Indian Art of the Future

When a living Indian culture arises out of the wreck of the past and the struggle of the present, a new tradition will be born, and new vision find expression in the language of form and colour, no less than in that of words and rhythm.

The people to whom the great conceptions came are still the Indian people, and when life is strong in them again, strong also will be their art. It may be that the fruit of a deeper national life, a wider culture, and a profounder love, will be an art greater than any in the past. But this can only be through growth and development, not by a sudden rejection of the past. A particular convention is the characteristic expression of a period, the product of particular conditions; it resumes the historic evolution of the national culture.

The convention of the future must be similarly related to the national life. We stand in relation both to past and future; in the past we made the present, the future we are moulding now, and our duty to this future is that we should enrich, not destroy, the inheritance that is not India’s alone, but the inheritance of all humanity.

CONCLUDED

READ

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4

Notes

- Pope, Tiruvâcagam, p. lxiii ; Nallasawmi Pillai, Sivagnana Botham, Madras, 1895, p. 74. ↩︎