Volume VI, Issue 1

Author: Beloo Mehra

Editor’s Note: Temple heritage is perhaps the most visible and material record of the spiritual evolution of Indian civilization. This article presents an overview of some of the ways in which a temple continues to embody and give a new form to the ancient Vedic spirit.

The Hindu Temple is not merely a congregational structure or a place of worship. It is the house of God (devālaya), the house of the Spirit. God is the Spirit immanent in the Universe and the temple is His abode. Stella Kramrisch, the well-known authority on Indian art history, suggests that the Indian temple is the concrete shape (mūrti) of the Supreme Essence. And thus it is both the residence and vesture of God. The masonry structure represents the sheath (kośa) and body. The temple is thus a monument of manifestation of the Essence.

The deep spiritual symbolism, the mesmerizing grandeur and the rich aesthetic seen in Indian sacred architecture has perhaps no parallel in the world. Traditionally, a temple had been at the centre of life in Indian villages and towns. From the great mountain and cave temples to the ones built in ancient cities in the plains, the diverse temple traditions are closely interwoven with the culture of this land. Cities and places of pilgrimage have grown up around temples, such as Srirangam and Rameshwaram.

Temple heritage is perhaps the most visible and material record of the spiritual evolution of Indian civilization. Through its concrete manifestation, a temple symbolizes and represents the deepest aspiration of the man. That is, to carve out a spiritual way of life that will unite the human with the Divine. This was also true for those who built the great temples all over this land. For the long line of the Sthāpatis and Sthāpakas, temple building was a religious dedication, an offering to the Deity.

Continuity of the Vedic Spirit

Kramrisch speaks of the continuity of the Vedic tradition in the temple architecture through the relation between form and performance. The sole concern of the Yajamāna or the sacrificer was his transformation through the strict performance of the Vedic rites at the altar. But in later centuries, an architect was entrusted with the architectural rites. And he performed them in enduring materials for ‘the sacrificer’, and for all those who might use the form in the future.

“Indian form, as far as the devotee is concerned, owes much of its efficacy to the never-forgotten equation of form with the visible equivalent of performance. The result is a transformation of the self.”

~ Art of India, Traditions of Indian Sculpture, Painting and Architecture, p. 19

The piled horizontal mass of the altar on which the sacrificial fire once burnt, over time became the basis and support of subsequent types of architecture where the Presence embodied in the monument was worshipped.

READ:

Indian Sacred Architecture and the Original Oneness

The prototype of the temple is the Agnikshetra. It is the sacred ground on which the Vedic altars are built. Subhash Kak explains the correspondence between the Agnikshetra and a temple.

“The Agnikshetra is an oblong or trapezoidal area on which the fire altars are built. During the ritual is installed a golden disc (rukma) with 21 knobs or hangings representing the sun with a golden image of the puruṣa on it. The detailed ritual includes components that would now be termed Shaivite, Vaishnava, or Shakta.

“In Nachiketa Agni, 21 bricks of gold are placed, one top of the other in a form of Shivalinga. The disk of the rukma, which is placed in the navel of the altar on a lotus leaf is in correspondence to the lotus emanating from Vishnu’s navel which holds the universe. Several bricks are named after goddesses, such as the seven krittikas….

“The Puruṣa placed within the brick structure of the altar represents the consciousness principle within the individual. It is like the relic within the stūpa. The threshold to the inner sanctum is represented by the figure of Ganesha, who, like other divinities, symbolizes the transcendence of oppositions.”

~ Subhash Kak, Art and Cosmology in India

The word Puruṣa literally means ‘person’, and it refers to the Cosmic Being. It is the body of God manifested or incarnated in the ground of Existence, divided within the myriad forms.

Sri Aurobindo on

The Inmost Reality of an Indian Temple

Kak further elaborates on the antiquity of the temple tradition and the use of religious iconography, both as a natural and organic continuation of the Vedic tradition. He writes,

“The Ashtadhyayi of Panini (5th century BCE) mentions images. Ordinary images were called pratikriti and the images for worship were called archa… Deity images for sale were called Shivaka etc., but an archa of Shiva was just called Shiva. Patanjali mentions Shiva and Skanda deities.

“There is also mention of the worship of Vasudeva (Krishna). We are also told that some images could be moved and some were immovable. Panini also says that an archa was not to be sold and that there were people (priests) who obtained their livelihood by taking care of it. They also mention temples that were called prāsādas.”

Another tradition complimented the tradition of the Vedic ritual — namely, the tradition of the munis and yogis. They lived in caves and performed austerities. From this tradition arose the vihāra. Kak surmises that the chaitya hall which also housed the stūpa may be seen as a development out of the agnichayana tradition, where within the brick structure of the altar was buried the rukma and the golden man.

The Residence of God

One of the technical terms for temple is Prāsāda which represents the dwelling place or a residence of God. In Samarāṅgaṇasūtradhāra we find a mention of 64 types of prāsādas classified under five different Vimānas. The latter are the aerial cars or palaces of the Gods. It is said that the Vimānas were actually the precursors of Prāsādas. A story in the Samarāṅgaṇasūtradhāra speaks thus of the origin of Vimānas.

Once Brahmā created five magnificent Vimānas for gods. They were colossal and made of gold and studded with precious gems. They were to be used for travelling in the air. Their names were Vairāja, Kailāśa, Puṣpaka, Maṇika and Triviṣṭapa. They were to be used by Brahmā, Śiva, Kubera, Varuṇa and Viṣṇu respectively. Brahmā then created so many other Vimānas like these, meant for the use of other gods such as Sūrya, etc. And each of these had its form in the likeness of the specific deity using them.

It is from these five shapes of Vimānas that later Brahmā created the Prāsādas. The text prescribes that temples are to be built in towns and are made of stone or burnt bricks.

Read

The Temple as Puruṣa

“Our ancient Indian temple is not just a technical, mechanically calculated end product but also a symbolic representation of a much wider concept; it is a lucid depiction of the entire cosmos as envisioned by the artist.

“Undoubtedly, it involves the highest mathematical calculations and engineering skill, but under the sheets of diagrams and equations, one finds the actual foundation of the architecture-to-be – the four points of a square is what makes the sacred geometry and these represent the cardinal directions. The area in between is a representation of the earth.

“Madurai is a case example and during the annual mass circumambulation that takes place, this ‘earth’ within is charged by the procession, so much so that the thronging devotees swear by the electrical waves perceivable in the air.”

~ Shonar, Of Past Dawns and Future Noons: Toward a Resurgent India, 2006, pp. 19-20

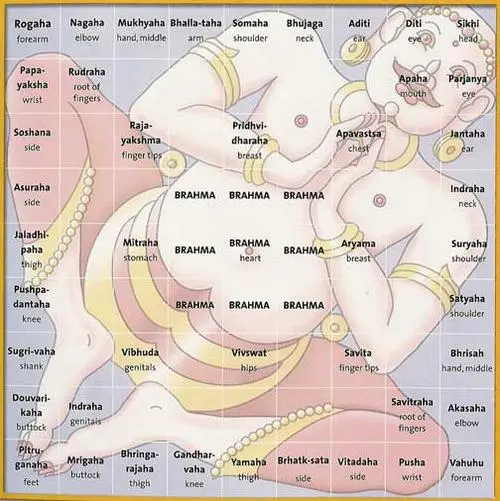

Vāstupuruṣa

Vāstu Shastra, the Vedic science of layout and planning of buildings, is the oldest known compendium on architecture. Developed between 6000 BCE and 3000 BCE, this science evolved over the course of time. One of the core fundamentals in Vāstu Shāstra is that Earth is a living organism, throbbing with life and energy. This living energy is symbolized as a person, the Vāstupuruṣa. The site for the temple is his field, the Vāstupuruṣa Mandala, is his body, and it is treated as such.

Vāstupuruṣa or Vāstudeva is the presiding deity of vāstu, of whatever is built on the earth. According to a story in the Matsyapurāṇa, Lord Shiva was once engaged in a battle with a demon named Andhaka and killed him. During the battle, some drops of perspiration trickled down from the Mahadeva’s forehead. A creature with a dreadful appearance was born from this perspiration. He immediately swallowed the blood of Andhaka scattered on the ground.

He then practiced severe austerities to please the Lord so that he could swallow down the three regions. Being pleased with his tapasyā, Shiva granted him the boon. This creature immediately attempted to cover with his body the three regions of heaven, earth and atmosphere, and fell down on earth. The gods along with the demons, rākṣasas, Brahmā and Shiva captured him from all sides. He remained pinned there where he was imprisoned.

Thus he came to be known as Vāstudeva and all the gods too resided there. The Matsyapurāṇa prescribes that any construction should be started only after invoking and worshiping the Vāstudeva. According to Bṛhatsaṃhitā, Vāstupuruṣa has his head towards the north-east facing the earth.

READ: The Aims of Indian Art

This Vāstupuruṣa, however, is not necessarily an actual picture of Man, encased in numerous cells or squares. Stella Kramrisch explains that it is a diagrammatic representation through symbols, of the field of co-ordinates, intersections, currents, the flow of energies in the subtle body of a human being. The Puruṣa, in these diagrams, is a term of reference. It serves as a means to locate several parts, within the whole. The body here is but a sphere of coordinated activities. And each part is associated with a particular function.

The Vāstupuruṣa Mandala represents the manifest form of the Cosmic Being, upon which the temple is built and in whom the temple rests. The temple is situated in Him, comes from Him, and is a manifestation of Him. The Vāstupuruṣa Mandala is also considered a bodily device by which those who have the requisite knowledge attain the best results in temple building.

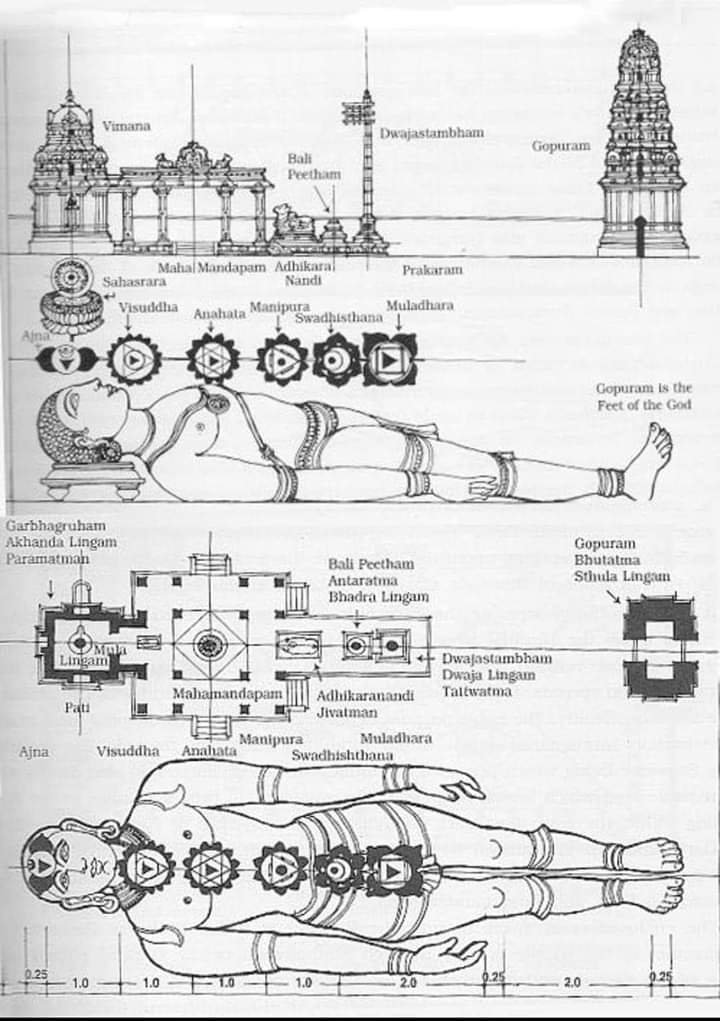

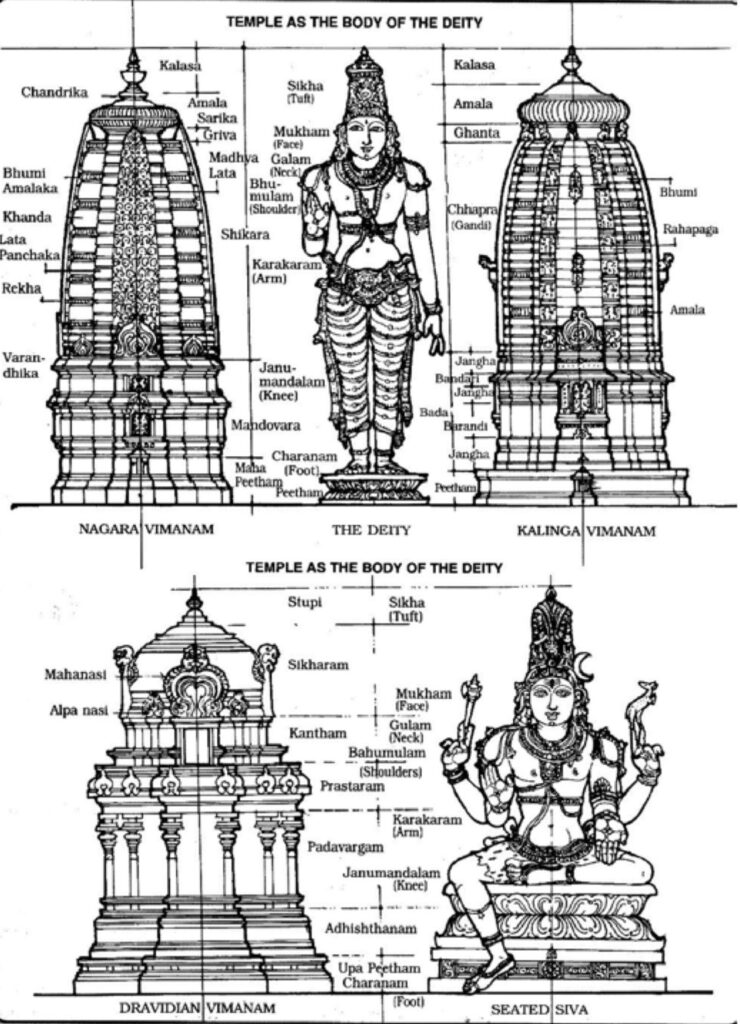

Embodiment of the Deity

A temple is seen as the body of God in his cosmic form, and the various worlds are located on different parts of his body. The bhūloka (earth) forms the feet of God, the satyaloka (the abode of Brahmā) forms His head. The other lokas (bhuvarloka, janaloka, svarloka, maharloka, tapoloka) form appropriate parts of his body. Similarly in a temple, the ground and the base slab represent the janaloka/bhūloka (earth), the inner courtyard represents the bhuvarloka (middle world), the pillars and the entablature going up to the ceiling represent the svarloka (sky). And the superstructure over the garbhagṛha represents the maharloka (abode of celestial beings) while the top knot or finial represents the tapoloka (the abode of the Ṛṣis).

As the embodiment or manifestation of the deity, the names of certain temple parts in Sanskrit are also anthropomorphic. For example, we have grīva (neck), skandha (shoulder), uru (thigh), and jaṅghā (lower leg). The chakras visualized in the practice of yoga are analogous to the stages up the vertical axis of the temple tower in the Drāviḍian style temple and it is marked by corresponding levels in the exterior.

The Vāstu texts also speak of the temple plan as homological to a human body.

In an article titled, Early Indian Architecture and Art, Subhash Kak (2005) gives a detailed and helpful description of the temple design. We know that the human body serves as the plan for all creation according to the Puruṣa-sūkta in the Ṛgveda. “The temple structure is homologous to the standing puruṣa as the śilpa-pañjara. At a lower level, a similar measure informs the proportions of the sculpted form, that may be standing or seated, and also of painted figures. This body at its deepest level is a body of knowledge.” (p. 23).

As a conception of the astronomical frame of the universe, the temple serves the same purpose as the Vedic altar, which reconciled the motions of the sun and the moon. The temple construction begins with the Vāstupuruṣa Mandala, which is a yantra, mostly divided into 64 (8 × 8) or 81 (9 × 9) squares, which are the seats of 45 divinities. Brahma is at the centre, around him 12 squares represent the Adityas, and in the outer circle are 28 squares that represent the nakshatras. This mandala with its border is the place where the motions of the sun and the moon and the planets are reconciled.

Nāgara and Drāviḍa

“The temples rise from a broad base: differently built according to specific types, they have their variation in time and place and their shapes were elaborated in many a school. As they are today in Southern India, their high super-structures ascend in pyramidal form, while in Northern India they fling their curvilinear faces towards a meeting point above the sanctuary.”

~ Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, p. 6

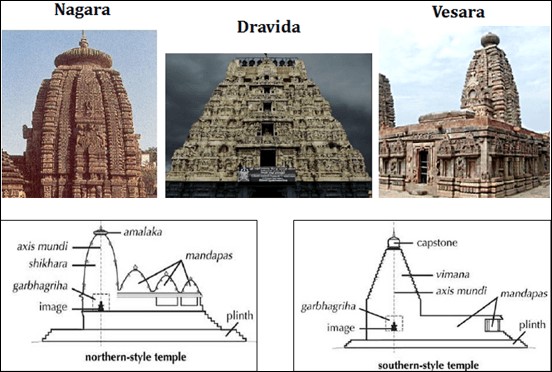

The temple building traditions broadly fall into two broad categories, the Nāgara associated with the Northern India, and the Drāviḍa of the Southern India. The texts also speak of another hybrid category, called Vesara, which in Sanskrit means “mule” emphasizing its hybridity. Within each of these broad categories, however, there exists a great variation in styles, indicating the wide experimentation that happened across time and space.

While the general principles described in Shilpashāstras and Vāstushāstras were always followed, great aesthetic independence was also encouraged. As a result the architects and builders often exercised considerable flexibility in creative expression by adopting other perfect geometries and mathematical principles in construction.

READ

“Temple-Tower to Heaven”, in Sri Aurobindo’s Savitri

The focus of the temple is the innermost sanctuary, garbhagṛha. This is typically a dark, unadorned cell, with a single doorway facing the east. Only the priest is permitted to enter the garbhagṛha to perform rituals on behalf of the devotee or the community. The mūrti in the garbhagṛha stands on its pedestal (pītha). A Vaishnava temple has an image of Vishnu, a Śaiva temple has a lingam. And a Devi temple has the image of the Goddess.

The garbhagṛha of the temple is enclosed by a superstructure. The nature of this superstructure makes the distinction between the Nāgara and the Drāviḍa type temple. In a Nāgara style temple, the mūlaprāsāda or the main shrine is enclosed by a curved spire called the śikhara. The Drāviḍa temple has a tiered pyramid form with a crowning top which is called the vimāna.

The pyramidal superstructure in the Drāviḍa style temple and the curvilinear one of the Nāgara style, both speak of their intimate connection with the philosophical or transcendental aspect expressed in an architectural content. To quote from Stella Kramrisch,

“Works of architecture serve a purpose; the Hindu Temple as much as a Gothic cathedral exceed their function of being a house or seat of divinity. While their orientation and expansion are in the four regions of space, their main direction, in the vertical, is towards God, the supreme principle, which is beyond form and above His seat or house of manifestation.

“From all these regions of space, from its walls in the four directions and their corners in the intermediate directions, the Prāsāda, rises bodily towards its High point, tier on tier, until diminished in its bulk, it forms the High Altar (vedī) on which is placed the crowning High Temple or the Āmalaka with its finial that ends in a point.”

~ Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, p. 179

Recursion

Typically, the temple structure is made of stone or brick, and is in the image of a wooden building. In case it is too difficult or expensive to construct a stone or masonry temple, it may be built of wood or any other available material. Kak explains this point as follows:

“The idea behind use of stone, but in the image of wood, — normally the building material for the residential house — is to project that the wooden, or human, nature of the conception is to find expression in the much more permanent stone just as the transcendent category of divinity is given the iconic expression derived from the human world.” (p. 25)

In the details of the superstructure, the śikhara or the vimāna, we see repeated forms and motifs, made to different scales. This represents another fundamental Vedic idea of recursion in reality. The recursion is also seen in the temple’s exterior decoration and composition. The basic compositional elements and grammar related to the joining of these elements are described in the relevant texts.

To quote again from Subhash Kak,

“The temple, together with its images, represents movement and change. This is achieved by the use of projection, extension and repetition across different scales.

“An extension at the centre of the body of the form is a bhadra; when located at the corner, it is a karma; located between the bhadra and the corner, it is a pratibhadra. Their use in different ways creates unique representations out of the basic Vāstu puruṣamandala.” (p. 25).

Sri Aurobindo reminds us that regardless of the outer differences, at the core of all temple architecture in India is her core spiritual vision — the Truth of the One. To appreciate this one requires a spiritual, meditative, intuitive method. Because that alone can facilitate an aesthetic interpretation or suggestion of the one spiritual experience. This truth of the One, in all its complexity and multiplicity, founds the unity of the infinite variations of Indian spirituality and religious feeling and the realised union of the human self with the Divine.

~ Design: Beloo Mehra