Volume VI, Issue 6

Author: Beloo Mehra

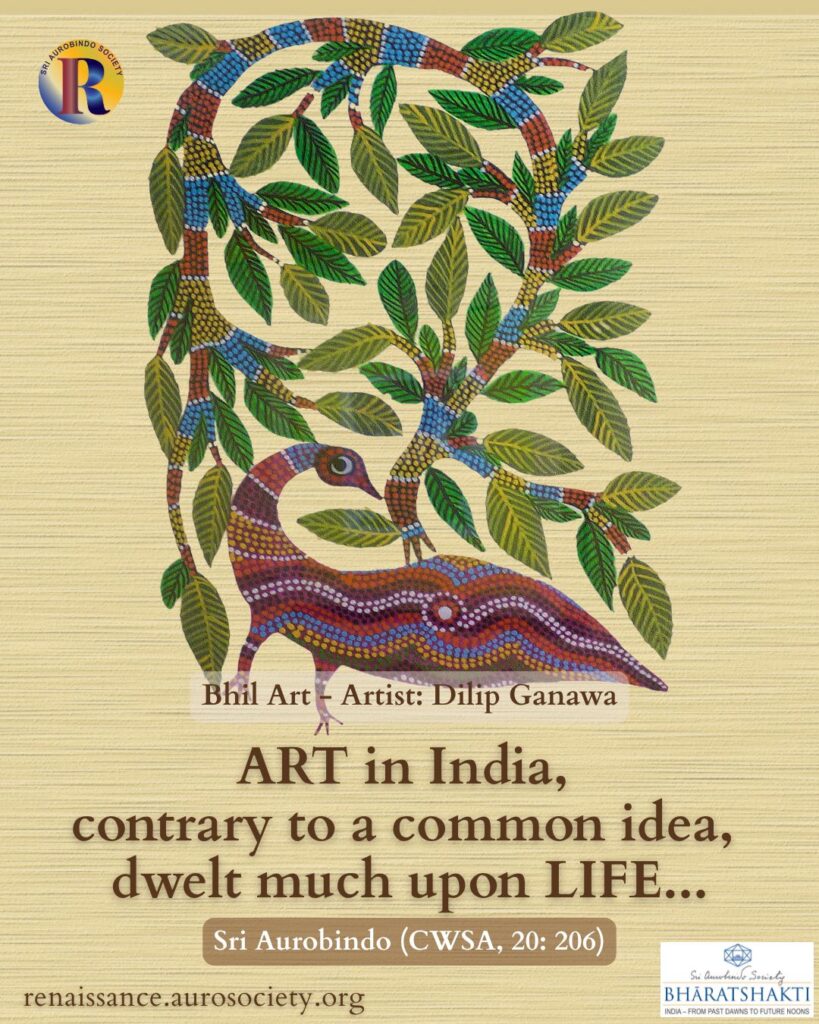

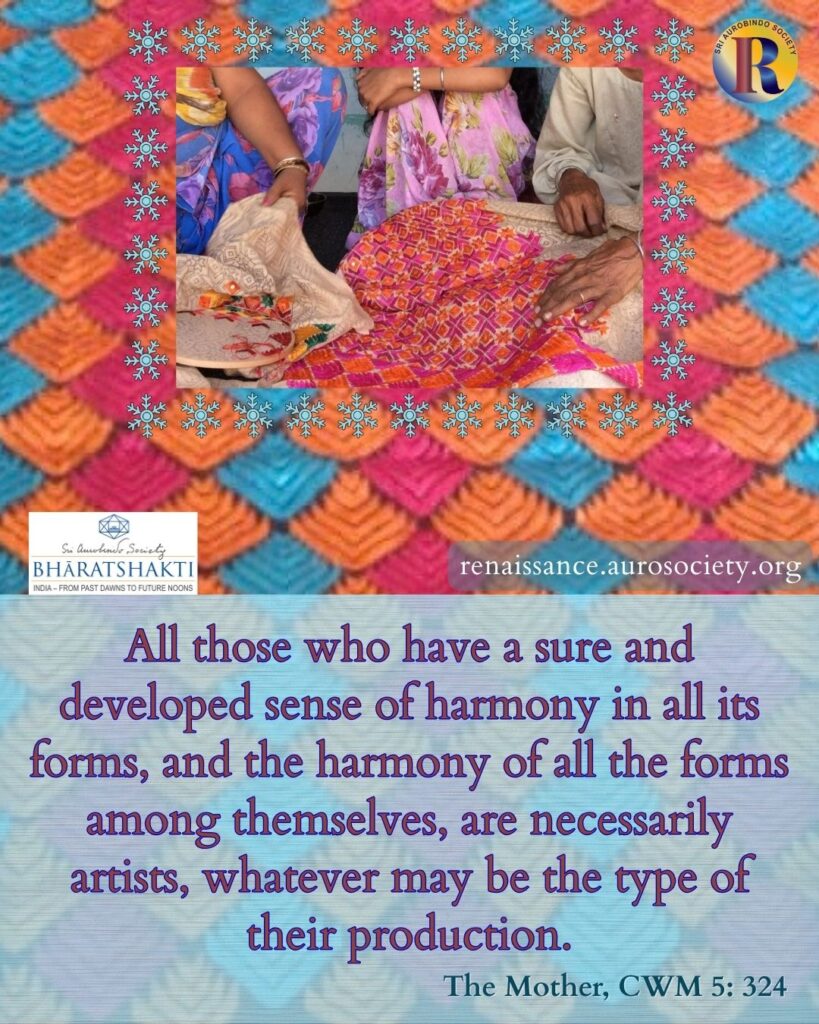

The Mother says that “the greatest nations and the most cultured races have always considered art as a part of life” (CWM, Vol. 3, p. 108). India is perhaps the richest nation in terms of having a great diversity of art forms. These are often grouped — somewhat ignorantly — under the label of ‘crafts’ or ‘folk art’. They include a rich variety of embroidery to ornate metal-craft, from pottery of different regions to elaborate painting styles.

Each of these traditional art forms has a unique aesthetic appeal. But more importantly, they are living and breathing examples of how art in India has always had deep connection with life. Only those parts of India “which are a little too anglicised have lost the sense of beauty,” says the Mother (CWM, Vol. 5, p. 340).

“Art in India, contrary to a common idea, dwelt much upon life”, says Sri Aurobindo (CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 206). The highest art has always been inspired by a spiritual view of existence and tried to express the hidden spiritual truth behind the outer form. But even when the artist intends to express some aspect of the outer life or simply to create a form for decorative purpose, there is still some sort of a suggestion or hint of some higher spiritual reality or a deeper psychic suggestion reflecting through the finished work.

Phulkari – History and Cultural Significance

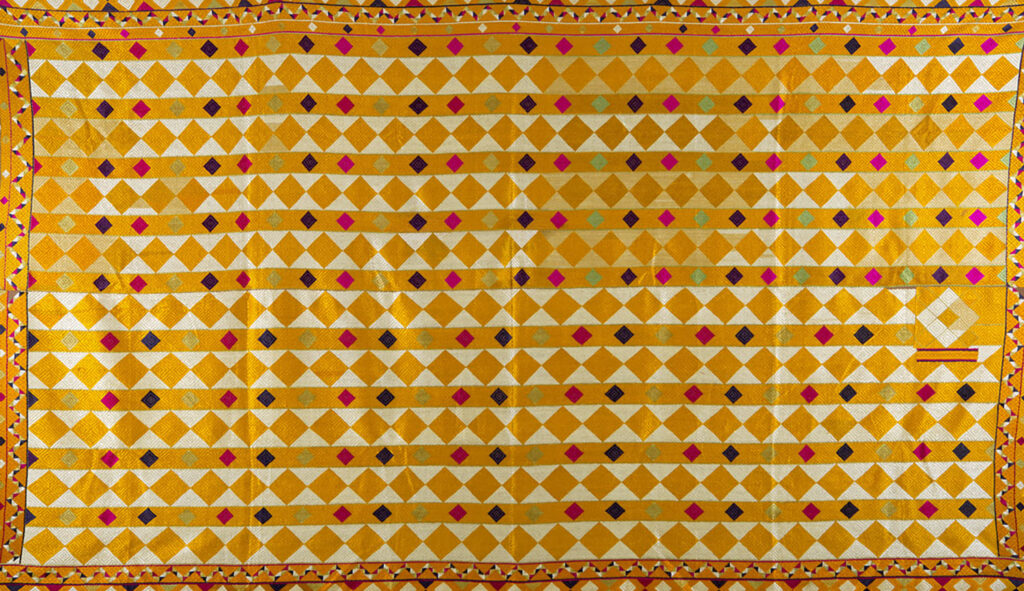

Let us explore the Art of Phulkari from Punjab. Historians generally trace the beginnings of Phulkari embroidery to 15th century, mostly done by women in Punjab and Sindh regions of the Indian subcontinent. While Phulkari is a name for a specific type of embroidery, the term also denotes the richly embroidered garment itself.

The term Phulkari translates into ‘flower work’ or ‘floral work’. But technically most common motifs used in Phulkari have more to do with leaves, wheat stalks and geometric patterns. But the skilled hands of an embroiderer arrange the patterns so perfectly that they look like flowers!

During Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s reign (1801-1839), Phulkari found much patronage and support and became an integral part of the cultural and economic lives of the people of Punjab. Much of Punjab’s cultural life was woven in these colourful threads. Punjab’s Partition in 1947 and its aftermath cast a strong negative impact on this art form.

Some historians believe that the art of Phulkari might have travelled with nomadic Jaat communities. This is because similarity of stitches and motifs is also seen in Kashida embroidery of Bihar, Heer Bharat of Kutch as well as Kasuti of Karnatka. Delicate and colourful threads of silk bringing together a diverse culture in a beautiful bond of oneness – what can be more beautiful than that!

Threads of Love

Phulkari developed mostly as a domestic art, passed on from mothers to daughters. The patterns, motifs and designs also passed from generation to generation. Over time, each family would develop its own characteristic style, and each woman was able to develop her own repertoire. In this way, Phulkari became an expression of the embroiderer’s feelings, hopes and dreams. Sometimes women would tweak the motifs slightly to express their emotions. For instance, a drooping plumage on the pair of peacocks could signify physical or emotional distance from the spouse, while a blooming one revealed the bliss of married life.

Phulkaris have traditionally been an important part of the trousseau of Hindu and Sikh brides in the Punjab region. To this day, a Phulkari odhni or dupatta is preferred by a tradition-conscious bride at her wedding. It is said that the moment a daughter is born, the mother conceives the idea of embroidering a special Phulkari, which she would present to the daughter at the time of her wedding. Thus begins the work of translating her vision into action, day after day, year after year, embroidering intricate Phulkaris.

She and her companions, the girl’s grandmothers and aunts, would create beautiful dupattas, odhnis, shawls, bedcovers, wall hangings, and other household linen. These are not just beautiful works of wearable and usable art; they are living embodiments of a mother’s love and devotion for her daughter.

Every time the daughter drapes herself or adorns her new home with one of these, the love and care of her mother and all the women in her extended family and neighbourhood comes alive with every silken buti she touches. These Phulkaris are preserved carefully and passed from one generation to the next, connecting hearts across time through delicate threads of silk and love.

***

All Art is a medium to express the Ananda, the Eternal Delight through Form. Sri Aurobindo says that an Indian painter or sculptor seeks the pure intensities of delight as he searches for the universal beauty revealed or hidden in all creation. The talented women of Punjab must have had same experience as their fingers would meticulously move the needle through weft and warp, and colourful motifs and flowers would soon be spread all over the fabric in such harmonious and pleasing patterns! A delightful experience of creating Art that would delight so many through the generations.

With a few specific types of stitches, motifs and geometrical patterns, Phulkari artists create a great variety of designs. Patiently working on a piece, repeating the same motifs and shapes, she makes no effort to break what may appear to an untrained eye a monotony of the pattern. But the eye of a connoisseur is, in fact, soothed by the harmonious blending of the outlines of flowers and leaves. The intricate borders give a sense of completeness to the finished work. Perhaps this is what Sri Aurobindo meant when he said that the excellence of the decorative arts and crafts of India has always been beyond dispute (CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 313).

The Deeper Suggestion

Bagh, Chope, Suber, Darshan Dwar, Chamba, Til Patra, Sainchi, Nilak, Surajmukhi, and Tota are some of the common varieties of Phulkaris. Each of them has its distinct characteristics and also the purpose for which it is to be used. For example, Darshan Dwar (Doorway to the Divine) is embroidered to adorn the walls of a room or space dedicated as an altar at home. These are also made as offerings for the local mandir or gurudwara. These are always done on red cloth. As the name suggests, they have a particular gate motif inspired by the pillars, carved arches and verandas of the temples.

This ode to the temple architecture in the design of a Phulkari is not unusual. Traditional arts all over India trace their origin back to the living religious and spiritual culture of the region. It is also reflected in the motifs and patterns used by the artists. Some textile historians believe that the Bagh variety of Phulkari actually emulates and re-creates the chowk – the multiple squares which create the grid that houses the nakshatras or nine planets, which according to astronomy govern our lives.

This sacred grid is the base upon which the home of the deity, the temple, would be erected surrounded by the houses of men and other areas of the township. The warp and weft of the cloth used for creating a Bagh provides the basis of the sacred grid. Upon this grid the embroiderer creates multiple squares, within squares, creating a rich and powerful pattern of the cosmos itself.

***

A couplet from Guru Granth Sahib, attributed to Guru Nanak Dev, speaks of the art of embroidery as an important passage of rite for a girl. “Kadh Kasida Pehreh Choli, Ta Tum Janoh Nari” is the said couplet. Literally, it means that only when a girl can embroider her own blouse, she will be considered an accomplished lady. But metaphorically it reminds one of making a psycho-spiritual effort to transform one’s outer being into a beautiful garment. That is possible only when one has painstakingly crafted a beautiful tapestry of the soul-lessons gained from varied life-experiences. This will create a deeper harmony within and without.

Origin and Continuity

The art of embroidery finds its roots in the Vedic times itself. In the Vedic literature the terms Peśas, Atka and Drāpi are used to denote embroidered garments. From the description of the Uṣas in the Ṛgveda, scholars infer that in Vedic times women wore clothes with embroidery done in golden threads. In a poetic description of the sunrise and sunset the Vedic rishi compares the horizon to the gold and red borders on each end of an embroidered cloth.

In Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa, the word Ārokha indicates clothes having designs of flowers, stars and other patterns. A woman who stitches Peśas is named as Peśakārī, both in Vājasaneya Saṃhitā and Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad. There are several other references indicating that art of embroidery was well-known in those earlier epochs of Indian civilizational history.

The continuity of embroidery as an art to elevate garments can be seen through references in Vālmīki’s Rāmāyaṇa. The poet speaks of the embroidered apparel of Sītā and Rāvaṇa. Megasthenes, at the beginning of the 8th century BCE, also refers to a type of embroidery or embellishment of fabric with designs using precious thread.

***

Several Sanskrit texts, including plays by Kālidāsa, mention silk clothes embroidered with swan designs. In a passage in the play Harṣacarita by Bāṇabhaṭṭa (7th century BCE) there is a reference to persons engaged in embellishing the hems of garments with the drawing of foliage in the upside-down manner. This may be one of the earliest references to the specific darning stitch used in the making of a Phulkari.

Needles have been found at all excavation sites in India dating from the third millenium BCE. At Harappa and Mohenjodaro archaeologists have unearthed figurines clad in embroidered garments. The sculptures of Bharhut and Sanchi, dating from the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, show figures wearing embroidered pieces of clothing.

A Renewed Interest

This history of embroidery in Indian culture leaves one in complete awe. But it is even more heartening that there is now a growing interest to know about various artistic traditions of India. The 2025 People’s Padma Awards is a testimony to this awakening. A large number of traditional artists from various parts of India have been honoured this year.

In 2021, seventy-year-old Lajwanti Chabra from Tripri near Patiala, Punjab was honoured with Padma Shri for popularising the Phulkari embroidery. Lajwanti grew up seeing her mother and grandmothers embroidering dupattas, bedcovers and other household items. By the age of ten, she was embroidering independently. Today she teaches the art of Phulkari all across India, including taking special sessions at National Institute of Fashion Technology. Her work has been exhibited at various places in India and abroad. And her children today are also accomplished Phulkari artists in their own right.

In this Issue

Since September 2024 we have been exploring different facets of ‘The Spirit and Forms of Indian Art‘. Several offline and online events have also been part of this exploration. We have touched upon a large number of topics and reflected on many dimensions of artistic traditions of India. This current issue comprising of 10 articles makes a total of 100 articles in the series; we may have a few more articles and events in the months to come.

Through an eclectic mix of offerings, this issue shines light on a rich diversity of expressions. From painting to poetry, from traditional to digital, from past to the future — readers will find here a rich Phulkari-like tapestry of creative expression and aesthetic appreciation.

- How to ‘See’ Indian Painting – Two Examples by Sri Aurobindo

- Sri Aurobindo and Indian Aesthetics – Part 3 (Sisirkumar Ghose)

- When Ustad Alauddin Khan Visited the Ashram (Samiar Kanta Gupta)

- Selections from Tagore, in Translation (Rabindranath Tagore)

- Appreciating Indian Genius through Exploring Traditional and Digital Arts (Narendra Joshi)

- Whispers Among Ruins: Angkor, Bhārata Shakti, and the Future She Beckons (Sunil Kumar)

- On Gond Painting and Changing Times (Beloo Mehra)

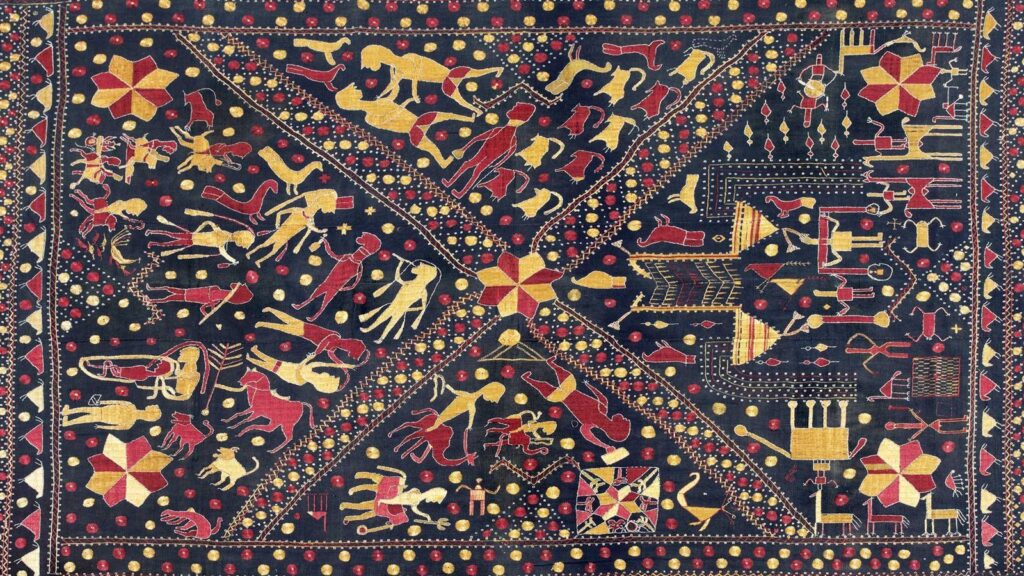

- Tantric Art as Visual Metaphysics (Narendra Murty)

- When A Walk in the Park Helps a Poem Blossom (Nispriha Sharma)

We hope our readers will enjoy going through the various offerings in this issue. As always, we offer this work at the lotus feet of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother.

In gratitude,

Beloo Mehra (for Renaissance Editorial Team)

~ Art selection and web design by the author